Latest Contributions

A Six-year Old’s Visit to Pabna: 1940

Category:

Tags:

Tapas Sen was born in Kolkata (1934), and brought up in what now constitutes Bangladesh. He migrated to India in 1948, and joined the National Defence Academy in January 1950. He was commissioned as a fighter pilot into the Indian Air Force on 1 April 1953, from where he retired in 1986 in the rank of an Air Commodore. He now leads an active life, travelling widely and writing occasionally.

Editor's note: This is a slightly modified version of article that originally appeared on Air Commodore Sen's blog TKS' Tales. It is reproduced here with the author's permission.

My story today is from the memories of a six year old.

Fragmented, somewhat disjointed, but gathered assembled arranged and decorated with fanciful imagination, and then cemented with love. To understand the story, however, the reader would need a few background notes that a six-year old is not in a position to provide. For a few minutes therefore I would have to hip-hop between my ‘me’ of today to the ‘me’ of 1940, as I lay down the back ground, often from hearsay information from an era a decade before I was born.

Background

The 1920s of India saw tremendous political ferment. The ‘Great War' had just ended - it had not yet been styled as the First World War! A new form of protest - Satyagraha - was being tried out in India, in Champaran in Bihar and in Kheda in Gujarat. The disappointment over the Montague-Chelmsford reforms of 1918 resulting in the diarchic Government of India Act of 1919 was converted to horror and anger by the passage of the Rowlett Act, and the massacre at Jalianwalla Bagh on 13 April 1919.

This fuming mass anger was channelled into the first massive truly national movement of non-cooperation by Mahatma Gandhi. The combination of Satyagraha with civil disobedience and non- cooperation fired the imagination of the then young India. Most of the jailed revolutionaries who were jailed or exiled to the Andaman Islands in 1905 /1907 were released from jail as a result of a general amnesty declared after the end of the War. They jumped right into this movement. Many government servants left their jobs and many students their schools and colleges as these were labelled as slave making factories.

Baba

Baba - my father - was one such student who left his studies and walked out. He was then a second-year student of the Calcutta Medical College. His father had passed away only recently, leaving his widowed mother and six younger siblings to his care. It was an awesome responsibility, but the strength of the call from the nation was irresistible.

Baba, like thousands of other young men at that time, wandered all over the country attending one political action to another, in the midst of a strong moderating debate launched by Rabindranath Tagore with the Mahatma about the validity of the method chosen by the latter. Then, one day in 1922, the Chauri-Chaura incident happened, leading to deaths even though the aim for nonviolent non-cooperation.

The Mahatma called the movement off. Hundreds of thousands of young men who had left their homes schools and jobs, forming the mass and the momentum of this huge movement, were left adrift. To say that most of them felt disappointed and let down would be an understatement. This multitude of youth had to re-invent their lives.

In the same time frame, a new religion was sweeping the world. Communism and Bolshevism were roaring along in Russia. The combined might of the victorious European powers was unable to stop that Juggernaut. Many amongst the wayward and confused Indian youth were attracted by this new philosophy. M N Roy and others of his time made their presence felt in International Communism. Many others however found that this new movement, in an attempt to decry organized religion, was bent upon destroying the concept of a godhead - of Paramaatman. In this process, they landed up denying the existence of Aatman or the human soul.

This deviation from fundamental Indic philosophy turned many of these men away from classical communism. They turned their whole energy away from politics into philosophy. Sri Aurobindo was one such well-known person. Many others also searched for the meaning of their lives through diverse other Gurus.

Baba found another medical practitioner whose philosophy attracted him. This person was Sri Sri Thakur Anukul Chandra. Thakur Anukul Chandra and his organisation, the Satsang, were for Baba like finding a shore for a drifting boat. He joined the organisation and became one of his earliest disciples. He re-joined the medical college and completed his medical studies, graduating from the Calcutta Medical College in 1924.

From then on, he never left the shadow of Thakur Anukul Chandra. The headquarters of Satsang was at Pabna in a village named Himaitpur. Baba rose in its hierarchy, and by 1938 he was appointed in charge of the district organisation for Jessore. The organisation held a quarterly meeting for its office bearers, styled as the ‘Ritwik Conference'. Baba thus became a regular visitor to Pabna.

My memories

Now back to my faint memories.

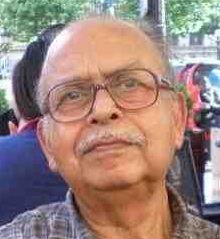

Tapas Sen. 1940. Jessore

For the Ritwik Conference due in early 1940, Ma wanted to tag along with Baba and visit Pabna. Thakuma decided that if her daughter-in law-could go for a trip, then she could tag along too. I was too young to be left behind, and my younger brother was in any case just a baby in arms. The party for the trip to Pabna thus became quite large.

The Second World War in Europe was in full swing. India had joined the War and was a very major supplier of war materials to Britain. The economy was booming, but there were also some attendant problems. Petrol had become rationed. Car trips became progressively difficult to plan.

There was no direct rail link between Jessore and Pabna. As a matter of fact, Pabna town was not on the railway map at all. The nearest railhead for Pabna was a place called Ishwardi Junction. However, even Ishwardi had no direct train from Jessore. Baba usually went to Calcutta and took a train to Ishwardi from there. This time, however, the large size of the party caused the routing via Calcutta to be burdensome. It was initially planned that we shall drive up to an intermediate junction station Darshana that was not too far. The plan however had to be jettisoned quickly, much to my regret. Two ladies plus two kids plus Baba plus luggage plus the driver was too much of a tight fit.

The fall back option was a bus ride up to Darshana. In those days, road transport was totally in private hands and was not really regulated. Roads were in a bad condition. Local buses were generally built on a 3-ton chassis. The public was quite class conscious. The tiny buses therefore arranged for separate compartments for ‘Ladies', ‘Upper Class' and ‘Lower Class'.

There was a new bus operating between Jessore and Chuadanga that went via Darshana. Baba's Man Friday, Amulya, was sent down to the bus stand to inform the bus owner that the upper class of that bus was to be reserved for the Doctor Saab on the appointed day. And the bus was to be re-routed to pick up the elite passengers from their home. In a small town in those lazy days, such dictates were common and were obeyed without question.

The so-called Upper Class in the bus was just a 5-seat upholstered bench placed athwart the bus just behind the driver's cabin, and sealed off from the front and rear by grilled partitions. We were a party of three adults, one child, and one infant. We had the compartment to ourselves. The only problem was a severe lack of legroom, which did not affect me.

The bus bumped along for two or three hours, and deposited us at the destination. We now had a lot of time on our hand, as the connecting train was available only late in the evening. We held an ‘Inter Class' ticket, and therefore we were entitled to the use of the ‘Upper Class' waiting room. Ma pulled out food packets of loochi and Tarkaari from one of her bundles, and we had a feast.

The afternoon wore on. I was bored. There was not much happening on the platform. I found it interesting to climb up and down the over-bridge staircase. After a while, even this climbing up and down became boring. I crossed the over-bridge and went down to the other side. A small road led away from the over-bridge in to the village.

Next to the railway line, a farmer was ploughing his field. He was quite a jolly fellow, constantly chattering with his bullocks. I gave him a smile, and we became friends. I have no idea as to how much time I had spent with the farmer. I suddenly felt that this news of having found a new farmer friend who talked with his bullocks must be shared with Ma.

I went over the bridge, and entered the waiting room. All of a sudden all hell broke loose. One man picked me up and ran out shouting loudly. At the other side of the platform, I spotted Ma running towards me, her saree half undone trailing behind her. Just outside the waiting room, Thakuma was shouting ‘he is here' to no one in particular. I was quite confused. Using free time to make friends was, I thought, a good idea! Of course, when one is only six, it is impossible to predict how an adult will react in a given situation.

Much cuddling and rona-dhona (weeping) ensued. It transpired that I had been missed by the elders for about two hours. Two trains, including one military special, had passed through the station in the interim period. Was I on of one of them? After the hubbub subsided, I was plied with sweets, and kept under strict supervision till we boarded the train and recommenced our journey.

We stretched out on the train's benches. The elders tried to get a little sleep. However, the excitement of the day had robbed me of my sleep totally. My little brother was fast asleep in Ma's lap while I kept on tossing and turning. At long last, she put the little fellow down and moved down to cuddle me. As was our usual routine, she told me stories of her own childhood. The stories were all known but each re-telling spawned a romantic magic of a fantasyland.

That night she told me the story of how her parents were travelling with her and their two other daughters on the same railway line from Darjeeling to Calcutta and how her two younger sisters had acted naughty. They had opened the door of a running train and had both fallen out on to the ground. How per chance it had been raining and the ground was soft, how my grandma pulled the chain to stop the train and how the train had backed up for half a mile to pick the two children up. Thrills, chills\; my imagination was running wild. How did they fall? How come they did not hit the stones lying about? And as I was going over the well-known story one more time, the train entered the Hardinge Bridge. It was one of the longest bridges in India. It stood over the Padma at Sara near Paksi. Goom Goom Goom Goom the wheels rolled over the line as I held on to Ma tightly.

We reached Ishwardi in the middle of the night. There was no means of transport at that time of the night to Himaitpur village that lay about five miles away from Pabna, which itself was a good fifteen miles from Ishwardi. We waited at the station for dawn to break. We took a Tomtom - a one-horse carriage. We reached Himaitpur in time for a late breakfast.

Traditionally, Baba was hosted by his close friend, Gopal Mukherjee, during his frequent visits to Himaitpur. This time however, we went over to another house. Our host this time was Krishna Prasanna Bhattacharya. To me it did not matter where I stayed as long as I was with my parents. However, there were many exchanges, muttered in hushed tones between Baba and Ma, as to why we could not put up with Gopal-da this time, and why, at the same time, we must make a formal call at his house as soon as possible.

I did not know at that time that tragedy had struck the Mukherjee family a while earlier. Mr. Mukherjee had died in a Railway accident. He was the Secretary to the Satsang organisation, travelling on an official trip when the tragedy took place.

I remember going to their house in a sombre mood, and being met by the bereaved widow. She had a son of my age, named Arunaditya, and a newborn child with her.

Mr Bhattacharya, who was our host for this time, was the president of the Satsang organisation. In his house too there was a boy my age. He was introduced to me as Kutum. We got along well. Bankim Chandra Roy, who was a whole time worker of the organisation in Jessore and a permanent resident of our household there, had been called up to become the new secretary. I was very fond of him, and he also loved me greatly. I was thrilled to find him at Himaitpur.

During our stay at Himaitpur, Sri Sri Thakur advised Baba that to buy a plot of land near the Ashram. "You will need it soon," Sri Sri Thakur said. It was a cryptic comment that puzzled Baba and Ma. They had just invested heavily in the new house at Jessore, and some loans were still outstanding on that. Still, they deferred to the advice of Sri Sri Thakur. We went to see the plot of land and a deal was struck. Little did anyone know at that time that the advice would be prophetic! (Editor's note: See Averting the Horrors of the 1943 Bengal Famine for the related story.)

We returned to Jessore within the week.

______________________________________

© Tapas Kumar Sen 2014

Add new comment