My Discovery of India -2

Category:

Tags:

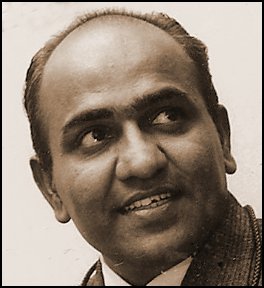

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's second not-for-sale book of his memories, Self-Portrait: The Story of My life, 2012. This website has several excerpts from his first not-for-sale book A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.This is the second of three sequential stories about his life after he left Mysore. The first story is available here.

Sleight of Hand

Living in a flat was a new experience. Not knowing Hindi, Meenakshi spoke only in English. Phatphatis, Delhi's famous motorcycle rickshaws, thrilled her. But the sight of a Sikh drying his hair after a bath in the winter sun puzzled her most. She had never seen a Sikh before. But in course of time Delhi became a pleasant experience. Kuppanna (who shared the first floor space of four rooms with me) and I had agreed to run a common kitchen. Kannaiah Lal Ji, a Garhwal Brahmin, had been employed as the cook. This saved Meenakshi from starting a kitchen immediately after her arrival. Kannaiah Lal had worked earlier for some South Indian families in Delhi and had learnt cooking. Meenakshi loved the change from rice and rasam to dhal and roti. Kuppanna too got married to a girl named Padma from Mysore. Saigal, the owner had just four of us as his tenants on the first floor. There was also a barsaati room on the roof in which a third tenant lived.

Saigal Saab was a former Railway employee, who worked as stores manager at the Tundla junction of the Northern Railway. Soon after his retirement, he had bought this property from the lump sum money he had received as retirement benefits. He lived in the ground floor with his family, which consisted of his wife, son, grandchildren and a divorced daughter and her son. He had kept for himself only three rooms and had rented the fourth (below ours) to Vishwanathan and his wife, a Tamil couple, who had a daughter. Vishwanathan worked as a stenographer in a private company. They were not well off but somehow managed with a meagre salary.

A short, stocky man wearing thick glasses, Saigal was painfully frugal. Very fond of money, often he sat on a charpoy in the winter sun holding his bank book close to his eyes, to check the entries in his account. We derived a vicarious pleasure in watching Saigal from our balcony haggle with the Sabziwallah (vegetable seller) and buy vegetables. He would closely examine every item, and taste bits of some of them like green peas, carrot, radish etc. before deciding what to buy. If he found the vegetable seller talking to another customer, his hands would pick a carrot or two and quickly transfer them into his bag. He was a confirmed kleptomaniac. Whenever his wife sent to us some special dish she had prepared, we looked for the two letters N.R. carved on the metal container. Doubtless, it was an item that Saigal had misappropriated from the Northern Railway. In case he came up to talk to us, we made it a point not to leave him alone. He had no servants. His daughter had to sweep and clean the house every morning with minimum amount of water. At night, he would prowl all over the house switching off lights and fans. Just the sight of unspent money gave him all the happiness. We liked him despite all this. He liked us too. My wife remained his Beti (daughter) for as long as we were there as his tenants.

Mahalingam Iyer

Barely a few months after the wedding, I went again to Madurai, not accompanied by my wife, but in the lively and cheerful company of Khushwant Singh. We were on a tour of the country to collect material for the journal. Finding Madurai on the itinerary, I was pleasantly surprised. It was an official visit. We had been booked at the Circuit House. Though our stay in the town was brief, we had enough time to go round the city, see the temple in great detail, and even accept a dinner invitation from Mahalingam Iyer, my father-in-law.

Mahalingam Iyer, a civil engineer, had settled in Madurai with his family after he had to quit his job when he was barely fifty due to a sudden stroke he suffered. He had bought a modest house - 13, Somasundarapuram Agraharam - in the Yanekal area of the town right on the bank of Vaigai, the city's famous and unpredictable river. By the time I came into the family as his son-in-law, he had recovered well and was able to manage his movements within the house and outside using a walking stick and even talk slowly with a slur. The Agraharam was a blind alley with tiled houses on either side with access only from the road that lead to the river. He lived in the house with his wife, Saradambal, and Lakshmi, the unmarried daughter. Mr. Iyer had specially summoned his eldest son Raman from Madras to help organise the dinner for us and play host on his behalf.

Mahalingam Iyer, a civil engineer, had settled in Madurai with his family after he had to quit his job when he was barely fifty due to a sudden stroke he suffered. He had bought a modest house - 13, Somasundarapuram Agraharam - in the Yanekal area of the town right on the bank of Vaigai, the city's famous and unpredictable river. By the time I came into the family as his son-in-law, he had recovered well and was able to manage his movements within the house and outside using a walking stick and even talk slowly with a slur. The Agraharam was a blind alley with tiled houses on either side with access only from the road that lead to the river. He lived in the house with his wife, Saradambal, and Lakshmi, the unmarried daughter. Mr. Iyer had specially summoned his eldest son Raman from Madras to help organise the dinner for us and play host on his behalf.

In the evening, Raman came to the Circuit House to escort us to Somasundarapuram Agraharam. Since the car could not enter the alley, we stopped at the entrance and walked up to the house. Curious women and children stood at their doors to see who the visitors were. The bearded gentleman walking with me with his colourful turban became the cynosure of all eyes. Perhaps they were seeing a Sikh for the first time. Mahalingam Iyer dressed in his pants and a shirt waited at the door with the walking stick in hand to welcome us. It was already dark. The hall was lit by a solitary electric bulb. We were asked to sit on a teak bench and my father-in-law sat in his favourite easy chair facing us. There was no other furniture. I introduced Khushwant to Mahalingam Iyer, his wife Saradambal, who stood at the kitchen door, and to Lakshmi, my sister-in-law. She was specially dressed for the occasion in a Kanchivaram silk pavadai and blouse with a bunch of fragrant malli in her plait.

Khushwant, unable to converse in Tamil, spoke a few words in English, got up and walked up to the wall to see the framed family pictures and those of gods and goddesses. I walked with him and explained the layout of the house. A large mirror fixed at an angle on the wall at a height facing the main door interested him. He asked me whether it had any Vastu significance. I turned to Raman who explained that it had been deliberately done so that his father sitting in his easy chair near the main door could see the reflected image of anyone coming into the home. If it were an unknown visitor, he would urge his daughters to leave the hall and go in. He didn't want to expose his pretty girls to utter strangers. This arrangement worked well even when a close friend came home. Mahalingam Iyer, seeing him early in the mirror, would shout a wholehearted welcome to the friend well before he entered the hall.

Soon the dinner, a traditional South Indian meal with additional items like idlis and chapattis, especially for Khushwant, was laid by Lakshmi in stainless steel plates placed on a teak bench. We sat for the dinner on another bench facing the plates. Khushwant wanted to know the names of all the items served and loved the hot idlis and coconut chutney, which kept arriving from the kitchen in a relay. We enjoyed the meal. When it was time for us to leave, Raman brought a huge well-packed carton and placed it in front of us. Lakshmi explained that the package was for me and that it contained home-made items, my favourites, which were not available in Delhi. Khushwant looked at the luggage intensely, turned towards me with a mischievous smile and said: "Naga, please tell your mother-in-law that we are flying and not going in a bullock cart!" I told her in Tamil what he said. There was all round laughter and the unwieldy gift was loaded into the dickey of the car as we said ‘good bye' to the family.

Back home in Delhi after the tour, the visit to her home in Madurai became a frequent topic of conversation with Meenakshi. She wanted to know all that had happened that evening: what her father said, the colour of the sari her mother wore, and how her sister Lakshmi managed the evening dinner. She was thrilled to hear that all went well and that Khushwant loved the home and the dinner. I told her that my only regret was that I was not able to spend some leisurely time with her father talking about our life in Delhi.

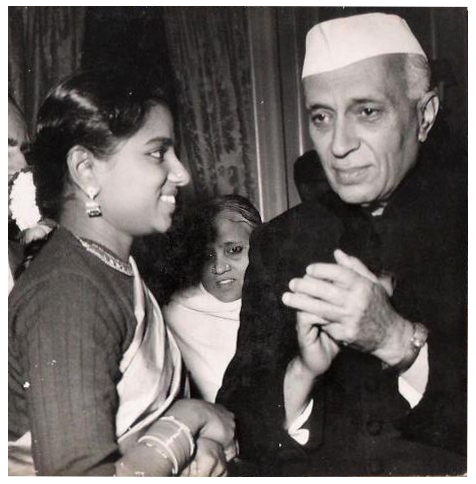

Breaking News

I thought of writing to my father-in-law thanking him for everything. This I did in style enclosing with my letter a photograph showing his daughter talking to none else but Prime Minister Nehru. The picture had been taken at an official reception to a foreign dignitary in the Capital to which we had been invited since I was part of the Capital's Press corps. Meenakshi had dared to go near the prime minister on her own initiative and talked to him. It seems that when the epoch-making picture reached Mahalingam Iyer, he rushed to the bazaar in a cycle rickshaw with the photograph in hand, got it framed and hung it prominently in the hall for everyone to see. Soon the picture made ‘Breaking News' in Somasundarapuram Agraharam.

For my wife, Mahalingam Iyer remained an ideal father. She loved talking about him. It seems that as a routine he sat on the thinnai (a raised place to sit outside) every morning and read the day's newspaper. Saradambal had to place a vessel full of rice and a pot of cold water next to him. He gave a handful of rice to all those who passed by begging for alms. The cold water was for thirsty workers who walked in the hot sun. He didn't get up and go in until there was no more rice or water left in the containers. Since he was not a pensioner, he looked up to his sons who were employed and lived elsewhere to help run the family. The postman delivered money orders from them every month. He kept a meticulous account of their contributions, and saved a good part of the money after meeting the household expenses. It was with this savings, built over the years, he celebrated his daughter's wedding.

Another significant aspect of his personality was the abundant love he had for his wife Saradambal. He disliked anyone talking ill of her. It seems his own mother, like a typical mother-in-law of those days, often taunted his wife with oblique references to the poverty of her parents, who had not provided their daughter with the minimum of gold and diamond-studded ornaments even years after the wedding. Though he didn't approve of his mother's stance, Mahalingam Iyer remained helpless. When the taunts became intolerable, he devised a clever method of putting an end to them. From the money he had saved, he got a pair of gold bangles made and sent it to his father-in-law in the village with the request that he should visit his daughter in Madurai and gift her the bangles making her believe that the gift came from her parent's home. No one else, including Saradambal, knew about the arrangement behind the seemingly appreciable action. He followed it up with additional gifts like a pair of diamond-studded ear rings or a mooguthi (nose ring, a must for all brides) on appropriate occasions. These graceful gestures to make his wife happy came to light only long after his mother passed away.

Music Buff

He was a connoisseur of music. There was a gramophone at home, "His Master's Voice", and a big collection of discs containing music by masters of the day like Musuri Subramanya Iyer, Chembe Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar and that of the then emerging young diva, M.S. Subbulakshmi, who can be known as MS. His mornings often started with a ‘MS' bhajan and, on special occasions like Pongal, he was keen that exactly when his wife Saradambal observed the ritual of placing the decorated pongal vessel on the stove at the auspicious time, the gramophone should play Nadaswaram by Sheikh Moulana, as background music to the ceremony.

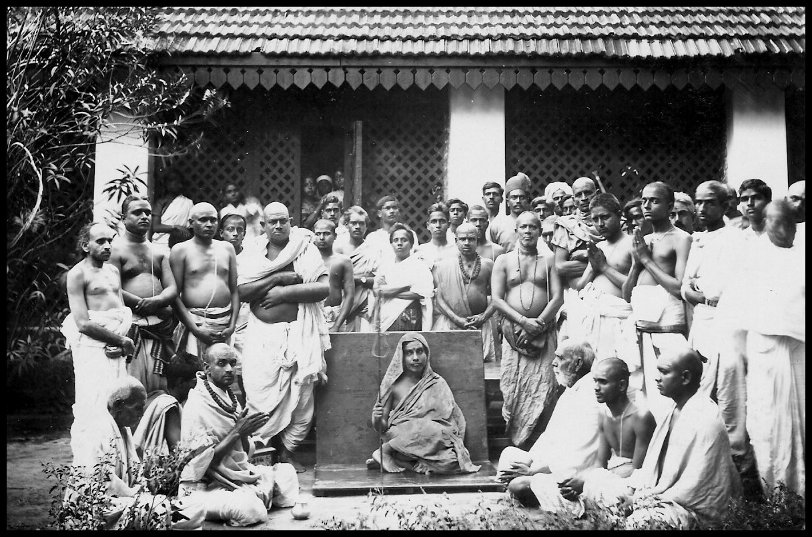

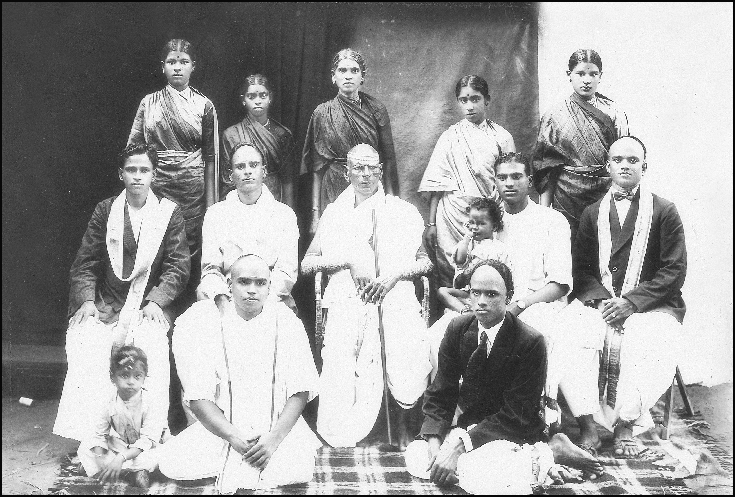

He had an extravagant passion for photography. This was evident from the number of framed pictures of him and his family and a pile of photo albums I found in a loft during one of my visits to the home. He frequented photographic studios to get himself photographed with his wife and children. He was keen that a photographer came home for recording important occasions. In the collection I have built from his albums, there are studio photographs of him in traditional and western attire with his wife standing next to him, perhaps taken in the early years after their wedding, and both of them with their children at various stages as they grew up. There is also a group photograph taken when he was posted at Anakapalli in Andhra showing Mahalingam Iyer and his relatives with the Shankaracharya sitting on a pedestal in the centre. He had invited the Swamiji of Kamakotipeetam to his home for performing a special ceremony to mark the birth of a daughter (Meenakshi) after three sons in a row.

In the pile of albums, I found a jewel - a photograph of young Mahalingam Iyer dressed as a fashionable lady in a sari with its end pinned on the shoulder with a brooch, wearing a pair of bangles, a wrist watch and, of course, wearing a suitable wig on the head to boot! It was fashionable in those days for young and handsome men to dress themselves as women and get photographed in a studio. This was perhaps one way of proving their good looks.

After my brief visit to Madurai with Khushwant, though I wanted very much to go there again, somehow, it didn't come through. Meanwhile Ratnam, Mahalingam Iyer's second son, got a good job with the Anglo-French Textile Mills at Pondicherry. The family moved with him to the former French town. The Madurai home was initially rented and was sold ultimately.

Delhi life

In Delhi Meenakshi found some Tamil speaking friends in the neighbourhood, who came over in the afternoons for a chat. Slowly, she began using some Hindi words in her conversations, her teacher being Kannaiah Lal, the cook. A special relationship developed between the two and they got on very well. I was a late riser giving myself just enough time to have a quick shave, bath, breakfast, and dress up before I rushed to catch a special peak hour bus to the office. Meenakshi would wait standing in the balcony for my return in the evening. Over a time, travelling by bus became somewhat tough and time consuming. Kuppanna and I thought of buying a transport. The Lambretta scooter, from Italy, had arrived in India. It was popular. The scooter was priced at Rs.1,600. It was difficult to save that kind of money from my salary. The office had a cooperative society. I borrowed the money from the Society on easy instalments and bought the scooter. My former roommate, Ramakrishna, came on a Sunday to teach me driving. We went to Shankar Road on the ridge for learning lessons. In no time, I began driving the scooter\; and after a time even to the office and back.

When Khushwant Singh became Editor of The Illustrated Weekly of India, he wanted me to do some interesting pictures of Nirad C. Chaudhury, the famous Indian writer, to illustrate a series of articles by him for the magazine. We had met the writer a few times at Khushwant Singh's place. Accompanied by Meenakshi, I went to his home. Nirad Babu had become a familiar figure walking the lanes and quadrangles of the Mori Gate area of old Delhi\; a thin, short, spry man in dhoti and kurta. He would usually don Bengali clothes at home. His suits and the hats were reserved for his walks. He was proud of everything British. He loved showing off his collection of a variety of items, especially those made in England, to his visitors.

As he talked with us, he opened the shoe rack and pulled out a pair of shining Oxford shoes and began explaining its special features. When he brought the shoes somewhat close to Meenakshi, urging her to see them, she boxed her nose and politely pushed the shoes back telling him "Nirad Babu, thus far and no further, please." Nirad didn't mind her comment. He had a hearty laugh with us, and continued singing in praise of the English shoes. Fame or position of people just didn't bother her. She was frank. She was candid. She was brave. She had nothing to conceal. She was true to herself. With a transport of my own, it became easy for me to take my wife around and show her Delhi.

One day we went to Raj Ghat to see the Samadhi of Mahatma Gandhi. I clicked a picture of Meenakshi as she placed a bunch of roses on the Samadhi. When we finished seeing the place, we relaxed on the green lawn for a while. As I clicked more pictures of her, I found her striving to tell me something about which she was feeling highly embarrassed. I asked her what was the matter for which came the gentle answer "I think I am pregnant" followed by an unforgettable smile. I didn't know what to say. I did what I generally do in such situations - click the camera. The result: my best portrait of her. The news reached her parents in Pondicherry. Months rolled. We did periodic trips to the doctor for check-ups and guidance. With every passing day, Meenakshi became more and more precious and a source of some special kind of happiness for me.

The time I dreaded promptly arrived. Meenakshi was in an advanced stage of pregnancy. She had to be sent to her parents place (Pondicherry) for the child birth and all the post-delivery care. Her brother Raman arrived to take her home. I wished her well and saw them off at the New Delhi Railway Station. Back home I felt miserable but tried to come to terms with the unavoidable situation.

Go to the third story in this sequence.

_______________________________________

© T.S. Nagarajan 2012

Add new comment