Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

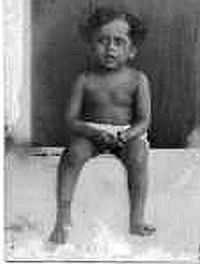

Early days: Jessore 1930s

Category:

Tags:

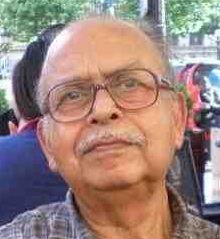

Tapas Sen was born in Kolkata (1934), and brought up in what now constitutes Bangladesh. He migrated to India in 1948, and joined the National Defence Academy in January 1950. He was commissioned as a fighter pilot into the Indian Air Force on 1 April 1953, from where he retired in 1986 in the rank of an Air Commodore. He now leads an active life, travelling widely and writing occasionally.

Editor's note: This is a slightly modified version of article originally appeared on Air Commodore Sen's blog TKS' Tales. It is reproduced here with the author's permission.

I have no recollections earlier than our being in the house (in Jessore) above the Chaurasta or the four-way crossroads.

Actually, it is amazing that I remember anything of Chaurasta at all, as I was really a small guy at that time. I was born in July 1934 and I now know that we left our hired house on the Chaurasta in mid – 1937. I should not really expect any memory of that age at all, but I find that in the rearmost recess of my childhood memory, I have a vivid picture of that house and I can recollect clearly my playful days there.

Tapas Sen. 1935. Jessore

Jessore (now in Bangladesh) was a small town in Bengal but was important enough to be a district headquarters. It had a District Magistrate and Collector, and a Police Superintendent. It had a district court and therefore a District Judge. It had an elected municipality and the townsfolk were active in its politics. It had a District Library, which my later memory finds to have been reasonably well stocked. It even had an electricity supply company, though, like most other houses on the Chaurasta, our house was not electrified.

Jessore had a District Board, an elected body, for local self-government. The District Board had, I think, three appointed executive officers. One looked after the administration, one was the district engineer and the third was my father, the district health officer. Of course, at the age of three or so I knew nothing about all these. I was the youngest of three children in a large loving family and that was enough for me.

Chaurasta was a busy place. The Station Road travelled north from the eastern end of the railway station for about a mile and a half or two. It ended at the edge of a very small triangular park. Dora Tana Road ran on the northern end of the park, more or less in the east-west direction. It marked the southern extremity of the town market or bazaar. Two other roads took off from the junction of Station Road and Dora Tana Road. If these had any given names, I never learnt about them.

Our house was old, a brick built two-storied structure. The plinth of the house was three or four feet above the street level. The house stood on the Station Road opposite the park. There were two or three shops at the ground floor facing the road. One of them, if I remember correctly, was a jeweller's shop. I do not recollect what the others dealt with.

We had to climb into a small corridor to get into the house. The floor plan of the house was in the shape of an L, with the inner edge around a small cemented courtyard. The entry corridor brought one on to a verandah along two sides of the courtyard. On the road ward side of the house, we had two rooms. One was used by casual guests, and the second was Baba's Baithak Khana (sitting room). (We referred to our father as Baba.)

Whenever Baba was in the Baithak, there would be other people sitting there talking with him. Discussions were loud and often animated, and the other people in the discussion were always identified as Baba's friends. On such occasions, the Baithak room would fill with cigarette smoke, heightened by the sweet aroma of Baba's cheroot smoke\; he used nothing other than the best from Havana. The table in front of him would fill with emptied cups of tea, and occasionally with emptied plates of snacks supplied by my mother. What they talked about is something I never learnt.

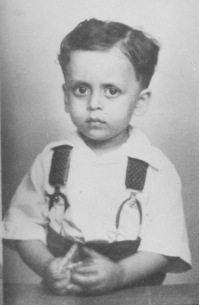

Tapas Sen with his mother. Jessore

The other arm of the L on the ground floor contained a large room with a multi-purpose use, but I think it was mainly a store. It had a long concrete shelf along the southern wall, where a de-deified idol (Editor's note: see below for meaning of ‘de-deified') of Saraswati was stored, awaiting its immersion when the next year's Saraswati pooja came around. That idol sitting serenely in one corner on the shelf always fascinated me.

On the eastern side of the building, there was a small tin shed that functioned as a kitchen. The edge of the sloping roof of the kitchen was low, and grown men or women had to bend to get into or out of it. I, however, could jump straight in from the verandah to the kitchen door.

One peculiarity of the kitchen was that it allowed a coconut tree to pass through its wall and roof. In times of rain, that part of the kitchen was always somewhat wet.

Next to the kitchen was a tubewell hand pump, and in the far corner was a dry latrine.

(For my younger readers, let me explain the concept of a dry latrine that was the usual sanitary facility in Indian small towns up till the time of Independence and the Partition. In one corner of every house there used to be an isolated room with a high platform floor. This platform used to have a hole in it, below which a tin canister was kept to collect faecal matter. The platform usually had a paired foot stand to let people squat accurately on the hole to drop their load without messing up the floor. A drainage system to carry the urine outflow and the washing water was usually provided. A whole community of cleaners cleaned out this mess twice a day every day carrying the stuff in buckets into disposal carts pulled by bullocks that went and dumped the stuff in designated places away from residential areas. It sounds horrible today and indeed, it was a very degrading practice, but this was our way of life then! Actually, running of this cleaning organization was one of the major tasks of the town municipality. Very few towns had piped water supply and practically no small town had a system of piped waterborne sewerage. To the credit of our leaders, the systems of dry latrines were banished from India soon after our Independence. I hasten to add that I saw nothing abnormal with a dry latrine system when I was a three year old. My revulsion grew much later.)

A narrow staircase, without any balustrade went up at the corner of the L. The lay out of the first floor was similar to the layout of the ground floor except that there were three rooms on the western side, and a small room on the northern side, leaving a small place for a first floor terrace. The staircase carried on to the top on to a balustrade edged terrace that was used for drying of clothes by the day and for evening strolls by the ladies of the house.

The first room on the western end was used by my parents, and I was allowed to share it with them at that stage. The next room was used by my two elder sisters, who would have been about seven and nine years old at that stage. My father's unmarried sister Kalyani, my Mejo Pishi, used to have the third room. Grandma, whom I called Thakuma, used the southern room during her visits from Barisal, the family homestead. She used to stay in Barisal with her youngest daughter, Kanika, my Moni Pishi, who was a student in a college there.

A charpoy was permanently placed in the verandah in front of the door to my parent's room. By day, it was the storage space for the extra bedding, and the dry clothes awaiting storage. There was a brown and black blanket which generally formed the base layer over which everything else was dumped. This blanket had a small hole somewhere in the middle. It was a great fun for me to get under this blanket, hide amongst the other clothes, and peep through this hole out to the strange adult world.

The terrace was the place where I could run about freely, but I was not allowed to climb up on to the terrace by myself. I was therefore beholden to my mother, or to Mejo Pishi, who would take me up to the terrace in the evening so that I could run about. This memory of mine has been reinforced by a snapshot of mine on the terrace that I have found in one of the old photo albums later in my life.

On the left side of the park, there was a small music shop from which Mejo Pishi used to buy her gramophone records. Sometimes she took me along for such shopping. The shopkeeper was an elderly gentleman, Nitai Dutta, who was very polite. Apart from running his record shop, he also undertook watch repairs. We always found him with a monocle stuck in his eye socket. He was ever ready to wind up a gramophone, and let us hear numerous records before Mejo Pishi would decide to buy one.

Most of the records sold were under the brand label of HMV. The labels were colour coded, perhaps according to their price. Most of the records at home were of red or maroon label with an occasional black one. There was another recording company with a name Hindoostan written over a blue label. It is my impression that the quality of their recording was not very high. The company did not last long.

The park was actually quite tiny. It was enclosed by a low brick triangular wall with a small gate on each side. I remember it very well because I used to look down to it from the first floor balcony overlooking the road for hours on end.

Tapas Sen. Jessore

I recollect one ceremony held on the park. By deduction, I now think that it was the so-called ‘Independence Day' celebration held on 26th January 1937. A small podium was erected. School boys and girls came marching in twos in clean white dresses singing songs. Some elderly people came and sat on the dais. Some girls came up on the dais and sang Vande Mataram. The elders spoke on the public address system erected. After about a couple of hours, every one dispersed. Throughout this activity, lots of policemen were standing around the park. For them and for the tired horses of the Ghoda-gadis (horse carriages) and Tongas parked on the third side of the triangular park near the entrance to the main bazaar, this activity did not seem to be exciting.

Snatches of memory floating through the mind make strange pictures, visible perhaps only to the one lost in that recollection. It is so difficult to decide as to what I think I remember is truly a fragment of my memory or it is a piece of brocade woven out of my imagination. And how would this fragment of a picture, pretty as it is to me, be of any interest to my reader of today? I don't really know. I find my recollection pleasurable: reason enough for me to put my fingers to the keyboard.v

_______________________________________

De-deification

We Hindus have a very convenient perception about the Almighty. He/She is one and is existent in every one and in everything. He/She has many names and can be interchangeably called by any of these names. He/She has many different forms, including 'formlessness', attached generally to the nature of the task He/She is about to perform, and the devotees are free to imagine the details of these various forms as the individual devotee desires.

The Almighty, in the imagined form, becomes a very personal possession of the devotee as a person or as a family, or as a group or class of people identified by location/caste/language/whatever label that the devotee desires to adopt. The devotees are free to create likenesses of this imagined Almighty as pictures/shapes/statues to pray to. Thus they become ‘idol worshippers for a bewildering number of gods.'

For the major Manifestations, worshipped by many and every day, idols of stones or metal are placed in temples that are looked after by professional priests. For individuals praying at home, miniature idols or pictures are located at a specified spot within the home. These spots are maintained by the householder or his wife personally.

There are traditions of ceremonially praying to a specific Manifestation on a specific day or days, once a year. For instance, Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge and learning, is prayed to on the fifth day of waxing moon in the season of Vasant (spring). For such festive prayers, idols are created by professional idol makers, following many detailed and intricate traditions.

These idols are then brought home or taken to a specific public space and are established there. The prayer ceremony is conducted at these locations by professional priests. The first action by the priest is to invoke ‘life' into these idols. This action is called praan pratishthaa, whereupon the idol becomes a deity.

Similarly, at the end of the ceremonial prayers, the priest performs a farewell action for the deity. That action is called Visarjan. Once Visarjan is invoked, the idol ceases to be a deity. It becomes a de-Deified clay doll. Handling this doll after Visarjan is a social nonreligious activity. Generally these idols are dumped into a water body with much fanfare.

______________________________________

© Tapas Kumar Sen 2014

Add new comment