Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

A tribute to my father – G T Parande

Category:

Tags:

Yashodhan Parande is a retired civil servant. He was born in 1951 in Nagpur and attended Hadas High School, with which both his parents were intimately connected as described in the accompanying article. After finishing his B.Sc. and LL.B., he qualified in Civil Service Examination in 1974, and joined the Indian Revenue Service (Customs and C. Excise) in 1975, and held various assignments in government of India. In the course of his career, he also obtained an MBA degree from Southern Cross University, NSW, Australia. He retired in 2011 as a Member of the Central Board of Excise and Customs, and has settled down in Delhi. He now indulges his passion for music, particularly Hindustani classical, exclusively as a listener and reading and travel (a fair bit being armchair travel!).

Baba, my father the late G.T. (Bapu) Parande, would have turned 100 on August 25, 2020 had he and my mother not been snatched from us in June 1995 in a road accident. Losing them together was such a wrench! And for me it was it was made worse by the fact that I was far away from home when the tragedy struck and could not be with them in their last moments. But, looking back, I realise that they went as they would have wished - in their shoes and together. It is impossible for me to think of one them without the other.

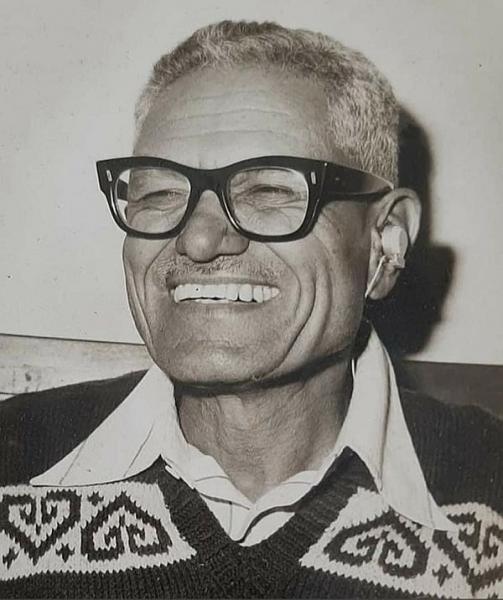

G.T. Parande. Nagpur circa 1985.

An entry in Baba’s journal dated August 21, 1947, says it all for him. “The finest motto for this life I have now found” he says, “is in:” (poem by Edna St. Vincent Millay)

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

The self-effacing man that he was, Baba rarely spoke about himself. But we do know that his early years saw the family fortunes swing from affluence to dire poverty. At the time of his birth, considering that it lived in a large bungalow on a 20,000 sq. ft. plot of land in a prosperous part of the town, the Parande family must have counted among Nagpur’s wealthier set. Nagpur was the capital of Central Provinces and Berar. The family patriarch then, his grandfather Keshav Govind Parande, finds a mention in the Birthday Honours List published in the Gazette of India Extraordinary on June 2, 1915 as a Rao Sahib. He is mentioned as a subordinate judge and deputy registrar in the Judicial Commissioner’s Court of C.P. and Berar at Nagpur, which in 1936 became the High Court of C.P. and Berar. He probably rose to be the Registrar of the Court before passing away in 1932.

Within a few years of his passing, the family fell on hard days. Why that happened is a story by itself.

For the present, suffice it to say that the large house in which the Parandes had lived along with three-fourth of the land on which it was situated had to be sold, and my grandfather with his family moved into what was the outhouse of the original property. My grandfather, T.K. Parande, while a widely read and talented man, wasn’t marked out by fate for success. He seems to have specialized in the teaching of what we would now call specially-abled – hearing and speech impaired – children. He was in fact sent on a scholarship for a year to England in 1920 to train for this – leaving for England shortly before my father’s arrival in this world.

He perhaps taught in a school for some time. However, he seems to have been unable to hold down a job for any length of time. He had also tried his hand at various businesses, including trading in timber, without much gain. I recall him from my childhood as an affectionate man, but one with a quick and fiery temper, which could not have been conducive to success in life. Around the time that the family silver, so to say, drained out, his business also collapsed.

The consequence of this adverse turn of fortune was that while my father enjoyed all comforts that a reasonably well-off family could afford while he was a school boy, his college education got interrupted. Now, he had to earn his way through his degrees, which were B.A. and B.T. (now B.Ed.). His first earning was as a stamp vendor around the age of 18, a princely sum of Rs. 2, which he dutifully handed over to his mother. He probably also tried his hand at stenography. He then took up a job in New India Assurance Company and moved to the town of Akola, near Nagpur.

In a talk titled “Down Memory Lane” he delivered in Sept. 1990 on AIR, Nagpur, he recalled that his friends demanded a celebration on his getting his first job, and he hosted a dinner for them at a restaurant. The cost of a sumptuous seven course meal for seven persons came to Rs. 16! And, he recalled, on getting a tip of four annas (twenty-five paise), the waiter was delighted and went away humming a popular tune from a Bengali movie!

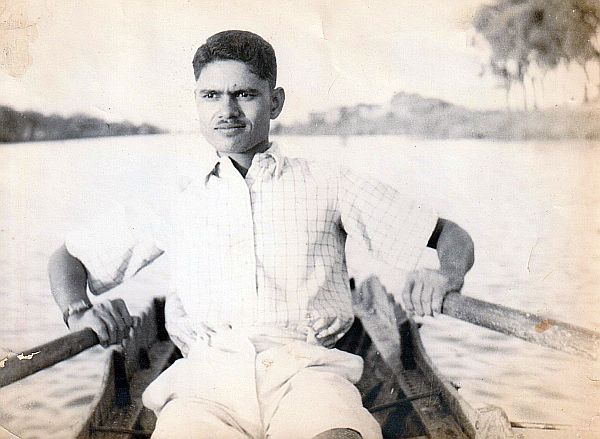

G.T. Parande rowing on the river Morna near Akola circa 1940

Soon, another event changed the course of his life. One of his school teachers, Mr. N.S. Hadas, whom he idolised, had quit his school over certain differences with the management. He decided to start his own school to be run on principles that he believed in and reached out to some of his former pupils, my father among them, to help him run the school.

Heeding this call, my father returned home and joined the school, which later rose to great prominence in Nagpur when we passed through its portals. Thus, began his career as a teacher. Although Mr. Hadas had a formidable reputation as a teacher, the school naturally began in a somewhat parlous state, there being little financial support then.

My father had answered the call of his guru, but it also meant that he had to quit a better paying and a steady job – not that he ever regretted it! Records show that the school started on the very day the Quit India movement was launched by Gandhiji, on August 8, 1942. Initially, the school ran from the Parande family home. But it soon had to find other accommodation as our old house went on the market, as I have mentioned above.

By all accounts, Baba was a popular teacher, judging from how fondly his students have always mentioned his memory to me. It wasn’t a paying profession though, a difficulty compounded by the fragile financial situation of the new school in the initial period. It was the idealism of Mr. Hadas and his band of devoted teachers like Baba that kept the school going in its foundational years.

This meant that he had to look for additional income and that is how he strayed into journalism. He was always fond of sports and was himself a good sportsman. He also wrote well. So, he started reporting on sports as a stringer for Nagpur Times, and was soon writing for four newspapers – three English and one Marathi. From April 1947, he worked exclusively for Hitavada, a very respected English daily of central India, that had been founded by the Servants of India Society in 1911.

It seems from his journal that he was conflicted over this decision. It was idealism that had led him to give up a steady and better paying job to embrace a career in education, and he agonised whether taking up journalism would come in the way of his cherished educational work. However, journalism had bailed him out of a dire economic state, and he felt that God had answered this for him.

He was able to balance the requirements of both jobs. From about 1946 till around 1963 he continued as a sports reporter as well as a teacher in Hadas High School. The first post-World War II Olympics were held in London in July 1948, after a gap of twelve years. Baba took that opportunity to travel to England and Europe to report on the Olympics for the Hitavada, and travel around parts of England and Europe. But more of that later.

Apart from sports reporting, he also did commentary mainly on cricket but occasionally for other games, for All-India Radio (AIR) Nagpur for a number of years.

My parents got married on January 1, 1951. My mother, Anuradha, whom we called Aai, was a remarkable personality in her own right. She had just finished her matriculation when she got married. Growing up in Dhar and Gwalior in Madhya Pradesh, she was learning Hindustani music under the tutelage of one of the disciples of one of the doyens of the Gwalior Gharana, Pandit Raja Bhaiya Poochwale. However, the early loss of her mother meant that the responsibility of helping her father run the household and look after three younger brothers fell on her shoulders. Her elder sister was already married. Then her marriage followed. She continued her education after her marriage, earning her BA in 1959 and her B.Ed. degree in 1963.

Around early 1960s Baba began to feel that with increasing demands of his journalistic duties he was unable to do justice to both his professions. In 1963 he resigned his teacher’s job and devoted himself fully to the Hitavada. From this time onwards, while he accepted many other responsibilities, he did not accept any other employment.

As we shall see, he came back to full-time teaching in a different way and at one stage, went back to being a school teacher. However, these responsibilities were accepted by him on an honorary basis. For the remainder of his life the salary he drew came from the Hitavada and from nowhere else. His connection with the school however continued as he remained a member of the Liberal Education Society that ran the school.

He thoroughly enjoyed his sports reporting days, though they brought little monetary rewards, as the payment was meagre. In a radio talk on the AIR in 1988 titled “Reminiscences of a sports reporter”, he mentioned his long hours and long journeys on a bicycle to cover various sports events across the city (sixty kilometres on some days), and the paltry amount that a sports reporter earned those days – a rupee a day for a column or two. But the reward was the welcome he got everywhere and job satisfaction, leaving little time to think of money. With his impish humour, he also mentioned another reward he won around this time, ‘A girl came around for matrimony too, though knowing that her husband was not likely to buy her even a single ornament in her whole life!’

The year Baba left the school, my mother joined as a teacher. Later, after her retirement as a school teacher, she earned her Master’s degree in Music.

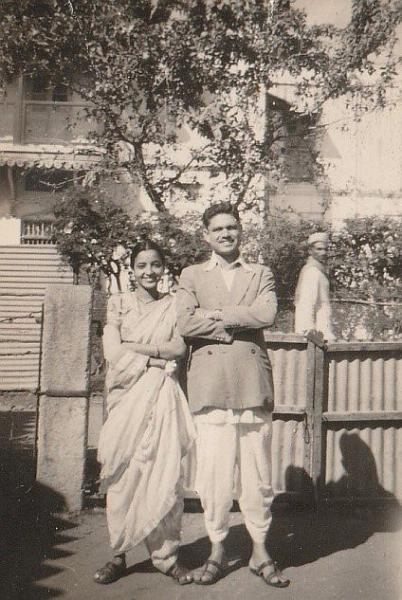

G.T. Parande and Anuradha Parande at the family home in Nagpur, shortly after their wedding in 1951.

I believe we are what we are because of our parents and our teachers. And in our parents, we brothers had both. Those who knew Baba will remember his perpetual youthfulness and his joie de vivre. His easy informality rapidly bridged the gulf of years. He had flourishing friendships with his students and younger colleagues, many of whom were my friends. He delighted in friendships and had a wide circle of friends across different ages and social backgrounds. He would often say to me that friendship was among the greatest gifts of life. I think he would have wholeheartedly agreed with this verse of Hillaire Belloc:

From quiet homes and first beginnings

Out to the undiscovered ends,

There is nothing worth the wear of winning

But the love and laughter of friends.

He really treasured his friendships and they spanned across the world. My brother Shyam, who travels widely for his work, recalls the many occasions, especially in US and Canada, when strangers would seek him out after hearing his name and enquiring after Baba. Many of them would be his old students or colleagues and would remember him with great affection.

As we grew into adulthood, our own relationship with him also transformed into respectful friendship. He encouraged everyone to express themselves freely, and that included his sons too. He had his views, which he expressed freely but never aggressively. I do not recall his ever having invoked paternal authority when we happened to disagree with him. And I have heard some of his students and junior colleagues say the same of him. Never was rank or authority invoked even in the face of disagreement and his effort was always to persuade with reason. I have rarely seen him lose temper. His injunction to everyone was, “It’s better to keep your temper than lose it”.

He had a great love of adventure and the outdoors. As mentioned before, he covered the XIV Olympiad held in London in 1948 as the Sports Reporter of the Hitavada newspaper. He was witness to the Indian Hockey team bringing home the Hockey gold medal. Around the same time, the Australia-England test series was also in progress, and he saw the fourth test at Headingly in Leeds, in which Don Bradman scored an unbeaten century (173 not out) to lead his team to a historic win over England. That century was the last of Bradman’s Test career.

After the Olympics, he travelled across England, visiting the Midlands, Yorkshire, Cumbria, Cotswolds and Wales and returned home via Denmark, France and Egypt. Much of his travels comprised hiking across the countryside, staying in youth hostels or YMCA hostels. He was keen to see the prospect of youth in the aftermath of World War II in these countries, and what lessons it had for the youth of the newly independent India.

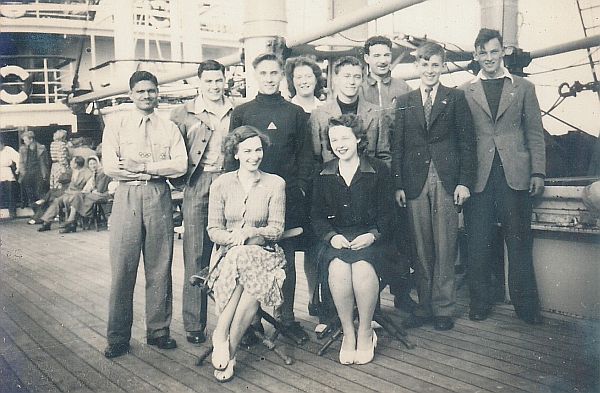

G. T. Parande (extreme left) on board the ferry Parkeston sailing from Harwich to Esberg, Denmark. August 1948

He spent the longest period of his European sojourn in Denmark, cycling across the country. International travel was not very commonplace in those days, particularly for Indians. Besides the desire to see new places and encounter different cultures, he has recorded that he was keen to make a deeper acquaintance with the Danish society as he believed that unlike the other European powers, Danish wealth was derived from her own soil and not from the exploitation of colonies.

He made numerous friends in the countries he visited and some of these friendships were lifelong. There is a picture of him in his book, rather smudged with age that shows him on his way to the Olympic venue, Wembley stadium, wearing a sherwani and the Gandhi cap, with a canvas bag slung over his shoulder. It makes him stand out in the crowd around him. I think it is emblematic of the emotions of hope and a newfound confidence of his generation – the generation that came of age in British India and matured into adulthood seeing the Sun set on the British Empire.

G. T. Parande on the way to Wembley Stadium, London, July 1948

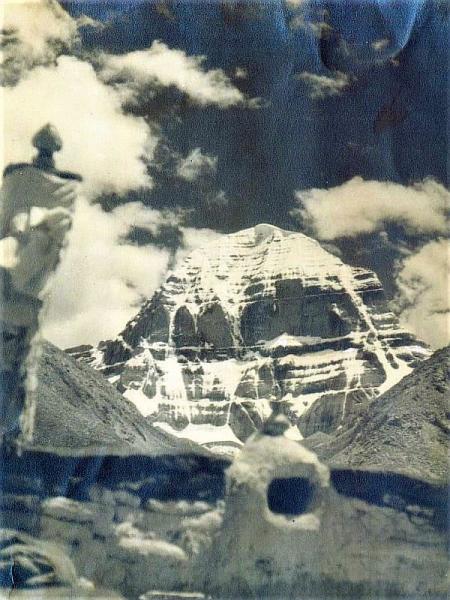

He must have been among the last few people to visit Kailas and Manasarovar before the Chinese annexation of Tibet in 1950. Inspired while reviewing a book on Kailas and Manasarovar by Swami Pranavananda, FRGS, he wrote to the Swami asking to join his next annual pilgrimage. The Swami kindly consented. In those days the trek commenced from Almora, and was far more arduous than today. The account of his trek is in his book Pilgrimage to Manasarovar, which unfortunately is out of print.

It was his sense of adventure rather than a religious quest that drew him to the celestial lake and mountain. As he explained in his book, his trip was a pilgrimage in a geographical sense and not to wangle salvation. He wished to go there not to meet God, but rather to admire and appreciate the wonders of His creation. And with his typical humour, he promised his readers that, should he meet Him there by chance, he would provide them with a full account of his interview with God– without the fear of contradiction!

He was fortunate to have travelled with Swami Pranavananda, remarkable person who left a deep impression on him. The Swami was a rare ascetic who did not allow his spiritual quest to interfere with his curiosity about the material world. The pilgrimage on which Baba accompanied him was perhaps his twenty-fifth. He had travelled to Kailas and Manasarovar by all possible routes and explored the area extensively, making meticulous observations and built a formidable reputation as a geographer. Visiting the region almost every year from 1928, he had extensively explored and traced the sources the four great rivers of this region, namely the Bramhaputra, Indus, Sutlej and Karmali, in the process disproving the claims of their sources made by the famous Swedish explorer, Dr. Sven Hedin from as far back as from 1908. In recognition of his efforts, he had been made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society by invitation.

Baba has recorded that he enjoyed his swim in Manasarovar every day of the parikrama (circumambulation). He mentions the Hindu belief that a parikrama of the holy lake entitles a person to perform his own shraddha, thereby relieving his descendants of that obligation and that some of them did perform that ritual.

The sight of the two lakes – Manasarovar and Rakshas Tal – and Mt. Kailas of course made a lasting impression on him. He could not have left them without a tear or two, when it was time to turn his back on them to commence the homeward journey. He closes his account of the journey with these words, “I am back among my people and the familiar surroundings again but in my prayers and in the recesses of my mind I live, and shall ever dwell, in the vicinity of the twin blue Lakes and the sublime white towering Mount”.

I do recall his mentioning to me that this memory was a great stress-buster for him – and he had more than his fair share of stress. In moments of stress, he had but to close his eyes and picture in his mind’s eye the turquoise lake and snow- clad mountain and the tension would dissolve!

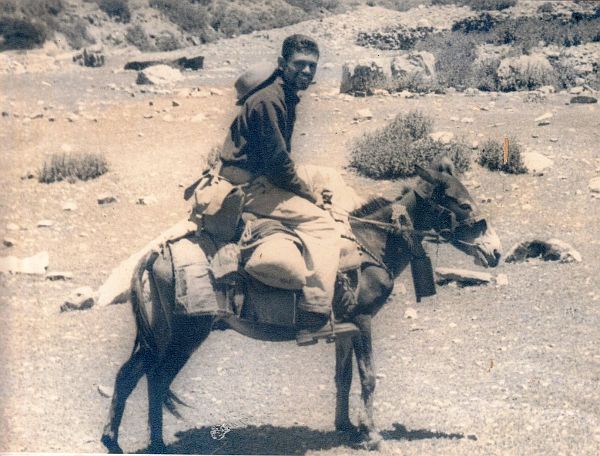

Some details of that trip would be of interest to today’s reader. Those who undertake this pilgrimage today are ferried by vehicles for most of way and the trip costs upwards of Rs. 1.5 lakhs. In 1950, starting from Almora, the journey was a little over 500 miles(800km). It had to be done entirely on foot and/or horseback and took about a couple of months. My father left Almora on June 7, 1950 and returned to Almora a little ahead of the rest of his party on July 28, accelerating his return as he had to be back at work in Nagpur on August 1, 1950.

Of the total of 514 miles, he covered 350 miles on foot and rest on horseback and on jhaboo (a cross between Tibetan Yak and Indian cow.) The total cost incurred by him, including rail travel (by the Gandhi class!) from Nagpur to Haldwani – the railway station from where you reached Almora by bus - and back, was Rs. 425!

Mt. Kailas Tibet 1950

G. T. Parande in Tibet 1950 en route to Manasarovar and Kailas

His love of the outdoors meant that we would often travel with his friends to spend weekends in the jungles near Nagpur. I have vivid memories of these simple pleasures. With his friends he had started an organization called Sahas, which encouraged youth to participate in a variety of adventure and outdoor activities such as 1-mile and 3-mile swimming races, trekking, 100-mile bicycle races and1,000-mile scooter rallies, and even angling!

The organizers were volunteers. There were meagre sponsorships those day and they had often to spend their own money. His own specialisation was swimming, which he loved and countless people in Nagpur, including almost all my schoolmates, thank him for teaching them swimming. My school, Hadas High School, which he had helped found and was deeply attached to, was in those days the first in the city to have a swimming pool. The remarkable thing about the pool was that it was the result of labour of love – the students, led by him and some of his teacher colleagues, had built it by shramdaan (volunteer work).

No mention of his life can be complete without the mention of his newspaper, the Hitavada, to which he had a lifelong commitment. He was truly a teacher and a journalist ‘to the manner born.’ He records in the introduction to his book My Olympic Pilgrimage, which is his account of his journey to the UK and Europe to cover the 1948 Olympiad for the Hitavada, that he ventured into journalism mainly to supplement the meagre income of a teacher.

But it was in journalism that he found his true calling. And once he joined it, Hitavada always had the first claim on him. Even when he accepted other commitments, such as helping to set up, and heading, the Nagpur University’s Department of Journalism and Mass Communication, teaching there and delivering lectures and classes in Journalism in different universities in the country as visiting faculty, it was never at the expense of the duty he felt he owed his newspaper. The Department of Mass Communication of Nagpur University recently honoured his memory by naming its new Seminar Hall after him.

He was very proud of the independent legacy of the Hitavada, founded as it was by the Servants of India Society. We were witness to his struggles as he and some of his colleagues stuck to it through the cycles of misfortune it suffered and folded up for a while. The difficulties they underwent and sacrifices they made, including his forgoing his salary for long periods of time, will need a separate chapter by itself.

In their effort to keep it afloat, for a short while they ran the paper as a worker’s cooperative. I remember his telling me at that time that this was only the second instance in the country of a workers’ cooperative taking over an enterprise, after Kamani Tubes. In two years, they managed to turn the finances around and managed to show a profit of Rs. 2,000. However, it was of no avail and in the absence of investments promised by certain investors coming through, the paper had to cease publication.

At that point, Baba had offers from the competition. However, he spurned them and decided to go back to his teaching. He became a school teacher again, though this time as a volunteer and not an employee. He began teaching in a village school at a place about 40 km from Nagpur named Khapa. He taught there for about two years, spending the week there and coming home on the weekends. By this time, three of us brothers were pursuing our careers outside Nagpur, with our youngest brother Dhananjay working in Nagpur. My brother Sanjay recalls going to Khapa on one of his visits home to pick up Baba on a weekend, and witnessing his popularity and the respect he enjoyed in that small rural community.

Soon however the fortunes of Hitavada changed for the better. Dhananjay remembers that sometime in late 1978 our house in Nagpur received an unexpected morning visitor in the shape of Shri Banwarilal Purohit, then a prominent industrialist of Nagpur, who is at present the Governor of Tamil Nadu. Shri Purohit was keen to revive the Hitavada and had approached Baba saying that he was the man to do it. Dhananjay recalls Baba mentioning that day as being one of the happiest days of his life. Thus, the ownership of Hitavada changed hands, new management stepped in, and my father steered the paper to its revival as its Editor.

He would be proud to see it flourishing under the leadership of his successors. So deep were his ties to Hitavada that even after he retired as the Editor, he remained connected with it in one capacity or the other till the end of his days – first as Ombudsman (the second one in the country after Justice Bhagwati became Ombudsman of the Times of India) and later as Editorial Advisor.

The mention of his visit to England reminds me of a couple of anecdotes he told me about that trip. While these stories would by themselves seem unremarkable, I think they bear re-telling because they open a window to those times. In July 1948, he found himself watching the fourth Test of Australia-England series at Headingly in Leeds. The Aussie captain was the great Don Bradman!

In the Press Box he found one of his idols, the legendary cricketer Sir Neville Cardus. My father sought and obtained an interview with him at his hotel. As the interview was getting over, he asked Sir Neville what his views were on the relative merits of cricket on coir matting and on turf wickets.

If the question seems strange now, it should be remembered that India had very few turf wickets in those days and cricket was mostly played on coir mats rolled out over roughly prepared pitches. In fact, I recall from my childhood that Nagpur had only one turf wicket at the Vidarbha Cricket Association ground, and we kids used to regard it a great privilege when we got a chance to play on that pitch.

Sir Neville’s response was terse. He rubbed the toe of his shoe on the door mat nearby and shaking his head said, “It’s not cricket, it’s just not cricket!”

Another story relates to a haircut. While having a haircut somewhere in the Midlands, he got talking to the barber, who was a demobbed soldier. It turned out he had been posted in India and that too at Kamtee, a cantonment near Nagpur. When he learnt his customer was from Nagpur, the two had a nice chat.

The novelty of that experience wasn’t lost on the young traveller from a newly (less than a year old) independent India. My father told me he couldn’t help thinking that just a year before that it would have been unimaginable in pre-independent India that he would be sitting in a barber’s chair chatting amiably while getting served by a white barber!

Journalism always remained his first love. He practised and taught it with passion. He was acutely conscious of the responsibility that profession entailed. Facts were sacrosanct. For him, it was a journalist’s duty to ascertain them first before forming any opinion. Equally important it was to be fair to all in the reporting; never should the rush for a story be allowed to get ahead of the facts. I think his generation of journalists was remarkable in that respect.

And that leads me to another story I heard from him. This one is from his early days as a budding reporter, possibly sometime around late 1950s or early 1960s, and relates to one of his uncles, my grandfather’s cousin, known in the family as Bhaiya saheb. I have childhood memories of this old gentleman, when he would have been in his eighties. He had retired from the judiciary, perhaps as a district judge and settled down in Nagpur as the head of a large joint family.

His eldest son, whom we knew as Nana kaka (kaka is Marathi word for uncle) had qualified as a lawyer, although he perhaps never practised law. To the extent I know, he had devoted himself primarily to the service of his father and practically functioned as his secretary. This was not altogether unusual in families with reasonable means and certain social standing in those days.

Anyway, getting back to the story, Bhaiyya saheb’s morning routine, after his bath and pooja etc., involved a meticulous study of newspapers, which Nana kaka would fetch for him. If anything struck him as being at variance with what he had earlier read, kaka would be asked to produce the previous reference and check the matter for veracity. Occasionally, my father would be summoned to his uncle’s presence and closely questioned on something he might have written in his paper – quite often something factual.

The conversation then would go somewhat like this:

“Nana, please fetch that (book or paper) and show it to Bapu. Now Bapu, have you written this piece?” pointing to a piece in the Hitavada.

“Yes.”

“Alright then, this is what you say (referring to the statement in the report). Now turn to page so and so, what does it say there? Is it not saying something different from what you have reported? Which one is true?”

The young reporter would then have to double down and convince his uncle either of the truth of his assertion or convince him that he had done his due diligence before reporting something as fact! I am sure this is the discipline his teachers and seniors in profession would have instilled in him. This would have been the sort of training that would have shaped him.

Epilogue

I often wonder what he would have thought of the current state of journalism in our country, had he been around. His students are perhaps better placed than me to judge that. I do think he would have been deeply disappointed with the general indifference to truth and fact checking, and the frequent mixing of news and opinion.

I am sure of one thing though - he would still have retained his optimism and shunned cynicism. I remember him as an indefatigable optimist. Neither age nor the undeserved hardship life often flung at him could make a cynic of him. It was perhaps this indomitable youthful optimism that sustained him through the stressful periods of life, which were many -that and the fact that he had a remarkably devoted and loving companion, my mother, by his side.

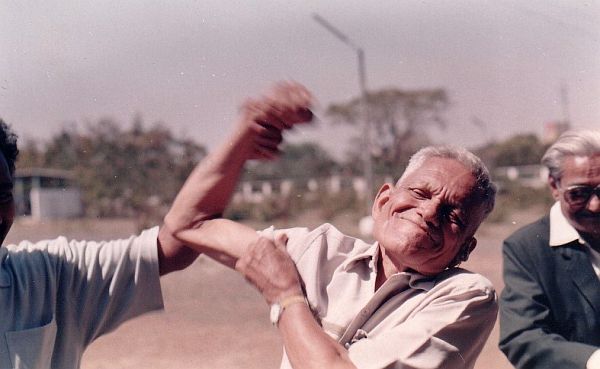

A nearly 75 years young G.T. Parande showing off! Nagpur circa April 1995. At the venue of a friendly cricket match.

I remember some of the conversations I had with him about the difficulties the Hitavada had to undergo. To the extent I remember, there were many factors, including financial problems and troubled management-labour relations that contributed to crisis.

However, Baba believed the two critical reasons for the paper’s failure, in common with many organizations which become moribund, were the failure of the management to understand the importance of technological change and invest adequately in new technology and the tendency of individuals to put their ego and interests above the interest of the institution. And he would emphasise this over and over again. In his own conduct he always showed acute awareness of both these factors. I realised the importance of what he had said to me as I progressed through my own career.

The other thing that comes back to me is what he had said about the two of his important influencers, Mr. N. S. Hadas, his teacher, and Swami Pranavananda, whom he accompanied on the pilgrimage to Kailas and Manasarovar.

Both were perfectionists, with a zeal for excelling in their chosen fields of activity. Mr. Hadas was a very popular teacher and inspired everyone to excel himself. His students loved and admired him and considered themselves fortunate to have had him for a teacher. The Swami was a very keen and meticulous explorer with a missionary zeal for accuracy. His monumental work “Kailas-Manasarovar” was recognized as an authority on the geography of that region. He disproved the claims of the famous Swedish explorer Dr. Sven Hedin, that the source of the river Brahmaputra was Manasarovar and proved that the river Sutlej originated from the neighbouring Rakshas Tal. They belonged to the class of people for whom work was its own reward. Their satisfaction was not derived from excelling all others around them in the spirit of competition but from the joy of reaching the ultimate in their chosen fields.

That is, I think, the most valuable gift he got from his mentors, which he in turn passed on to his children and students. And that was the way he lived, believing work to be its own reward and serving the institution that he believed had given him much. His was a life marked by simplicity and a strict adherence to the principles he held dear.

What tribute can his sons pay their father except to say that they have tried always to follow the precepts they imbibed from him! And I can say that for all my brothers.

_______________________________________

© Yashodhan Parande. Published February 2021.

Comments

Yashodhan's Post about his Father, Shri. G T Parande

Wow

Wonderfully articulated Raja.

Comment

This eloquent tribute is for

Extremely well written

Tribute to shri G.T.Parande

Reading the tribute is a

Reading your tribute to Mr G T Parande

Add new comment