Latest Contributions

My Discovery of India -1

Category:

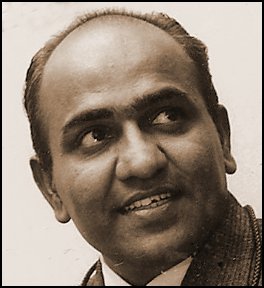

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's second not-for-sale book of his memories, Self-Portrait: The Story of My life, 2012. This website has several excerpts from his first not-for-sale book A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.This story is the first of three sequential stories about his life after he left Mysore in 1956.

I left Mysore for Delhi in 1956 after receiving the blessings of my parents. I couldn't guess what was happening in my father's mind when I prostrated in front of him. My mother drew a horizontal stripe of Vibhooti on my forehead and touched my head. I had to take the Janata Express, the cheapest train from Madras (now Chennai) to Delhi. The entire train consisted of compartments with only second class sleeping berths. It was a long journey, two nights and a day. It was winter and so the journey was pleasant. The train stopped at Gudur, the lunch station. A meal meant for me arrived in a covered stainless steel thali. The food was hot and delicious. The train chugged along slowly stopping at every station\; and after several meals and sleepless nights\; I got off at the New Delhi Station looking like a coal miner with all the soot that had settled on me.

Delhi was totally unfamiliar. I was in my early twenties. Apart from a short visit to Chennai to write an examination for a job in the Railways (fortunately, I was not selected), I had not travelled much in the country. In addition to Kannada, my mother tongue, and Tamil, my mother's tongue, the only other language I knew was English. I spoke or understood not a word of Hindi. Punjabi was foreign. Sikhs with their turbans, well-built physique and mesmerizing eyes appeared alien. I felt like a stranger in my own land.

There were a few families from Mysore who lived in Karolbagh. T. Kasi Nath, the well-known photographer, lived around the corner. He worked as a photographic officer in the photo unit of the Publications Division under G. Nanja Nath, another Mysorean. I was the third person from Mysore to join the two in the Government of India's Publications Division, but work exclusively for the Yojana magazine. I met them a few days ahead of my reporting to work in their homes. They were very happy to see me. Speaking with them in Kannada was reassuring.

Nanja Nath was indeed an early practitioner of photojournalism in India. He was the head of the photo cell that functioned in the Publications Division. Kasi Nath, a renowned pictorialist, was his right hand man. In addition to me, there were others - Harbans Singh, Moti Ram Jain and Tara Chand Jain - as part of the photo cell. Nanja Nath presided over his little kingdom like an emperor. He was short, square-faced, robot-like and physically unimpressive. He made it up by making every one realize that he was the boss. No one questioned his decisions. Kasi Nath was his faithful subject. Administratively, I was part of his set-up, but I worked under the Editor of Yojana. But, now and then, Naja Nath made me realise that he was indeed my boss. So I had to learn the art of tight-rope walking keeping my own estimation of people around me to myself. Barely a year or two after I joined Yojana, Nanja Nath mysteriously vanished from the scene. One evening he went out from his home supposedly to buy cigarettes from the shop around the corner and never returned. That was the end of Nanja Nath. He vanished from his kingdom like all dictators do - unsung and unadorned.

Room on the Roof

Initially, I shared a barsati (room on the roof of a building with a makeshift bath and a lavatory) with Ramakrishna, a bachelor like me, who worked as a Kannada news reader in the All India Radio. He was a simple and hard working person with a good sense of humour. It was very cold and I had no suitable woollen clothing. Ramakrishna had just one bed and a mattress. He had not bought a Razai (a thick blanket heavily filled with cotton) to guard against Delhi's cold. Instead he had a heavy woollen greatcoat, which someone had given him with which he covered himself in the night. All that he could spare for me was a make-shift mattress and no blanket. I had just a sheet over me. I shivered all night. Ramakrishna had shift duty. When he was on early morning shift, a car from the radio station would come around 5 am to pick him up. As soon as he heard the car horn, he would wake me up. Quickly I would jump up and stretch myself on his bed. He would put the greatcoat over me and leave. I used to wait for this moment when the greatcoat would fall over me to sleep comfortably until long after daybreak.

I had been told to report for duty at the Publications Division from where the Yojana fortnightly was published. The office of Yojana was located in the old Secretariat, presently housing the Delhi administration offices. The editor had a circular room in one corner of the building. Khushwant Singh had just returned to India after a long stay abroad and had agreed to edit the journal after much persuasion by the government. There was so much of corridor talk about him and his background. That he was the son of a knighted Sikh who had built a large part of New Delhi and that he was among the richest men in the Capital, who actually didn't give a damn for the salary he was getting, which was actually much higher than that of his boss, the Director, Mr. Mohan Rao, another Mysorean. All this had glorified him in the eyes of his colleagues. This gave him a special status in the office. Everyone looked at him with much awe as though he had just landed from space.

First Boss

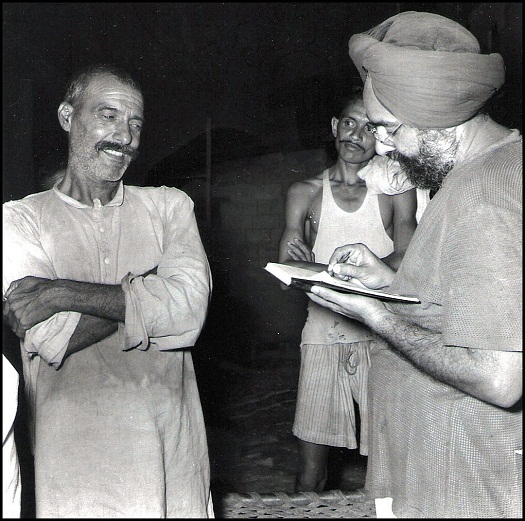

On my first day in the office, after completing formalities, I went into the editor's room. Khushwant sat behind a large table, covered with green flannel and a glass top. He was somewhat shabbily dressed in a blue sweat-shirt and a white turban, not very well tied. Even before I could sit down, he greeted me with a broad smile. Calling me ‘Naga' he said, "I have staked my reputation on you." His voice was sonorous\; his accent perfect. I fell silent and began shuffling my feet.

Some very talented and experienced people were on the staff of the magazine. Among them were Sheila Dhar, M.A. Husaini and Alamelu Krishnaswamy. I was the only one with no experience. Khushwant was always the first to arrive in the office and also the first to leave. He used to finish most of his writing much before all of us arrived. The first job for the day was the meeting in the editor's room. But, in these meetings, invariably much time was spent on office gossip. Khushwant, an excellent raconteur, used to regale us with jokes, mostly concerning the colleagues. This is why none of us missed these meetings. He was also very informal and utterly unbureaucratic. Though a peon sat on a stool outside his room, he seldom pressed the bell to call him. Also, he never sent for us. Either he called us on the phone or personally came up to our rooms. He hated files and finished answering long official notes scribbling a word or two like I agree" or "I don't agree". He never dictated any notes or letters to his secretary. He wrote out everything in long hand, which only his secretary could decipher. It took some time for us to get used to his scribbling. Travelling widely in the country and working with him brought me close to Khushwant, which resulted in a warm and enduring friendship.

The salary I was getting was not big but good enough to spend on some comforts for myself and spare a part to my mother. There was no need to continue living with Ramakrishna in the barsati. I looked for a room for myself and found a large one with a bath attached on Rohtak Road, near Karolbagh. The rent was a mere Rs.75. I furnished the room with rented furniture from Banerjee Brothers in Karolbagh, and enrolled myself as a regular boarder with a South Indian mess in the area. But there was the problem of walking all the way to the mess and to catch a bus in the morning to reach the office in Old Delhi. I needed to move closer to the mess and the bus stand in Karolbagh.

I began hunting for accommodation in the evenings. Punjabi house owners preferred Madrasis (as they called all South Indians) because they found them reliable. But there was a hitch\; bachelors were excluded. Luckily, I found a two-room facility on the first floor of a building owned by a former Railway employee, Mr. Saigal, who lived below on the ground floor. The first floor actually had four rooms with a bath and a lavatory, which I had to share with S.R. Kuppanna from Mysore, who worked in the Indian Standards Institution. I felt comfortable in the new home.

Eating out was no problem in Karolbagh. There were many South Indian messes, who served breakfast, lunch and dinner on a monthly charge. Rangarajan, my schoolmate in Mysore, who lived near, ate in a mess called "Chami Mess", well-known in the area. He introduced me to that mess\; and we began eating there on a regular basis. We used to finish lunch in a hurry before leaving for the office in the morning. Dinner was not hurried. We were good eaters, who cleared mountains of rice and rasam or sambar in a jiffy. We loved vegetable curries and invariably asked for repeated helpings. After dinner, we ambled towards home, helping ourselves on the way to a large lota of hot milk with cream floating on top, at the Punjab Sweet Shop on Ajmal Khan Road. We loved chewing paans. The nightcap was generally some 15 to 20 paans smeared with chuna and chewed with thin slices of betel nut. Rangarajan was an able singer of Carnatic music. He had undergone rigorous training with a guru in Mysore. On Sunday nights, there were mini concerts at home with Rangarajan singing and I accompanying him on the mridangam, which was nothing but an empty cardboard box. I owe my ability to enjoy classical music today to Rangarajan and those impromptu music concerts at home in Karolbagh.

I must mention here that, much to our disappointment, our gluttonous adventures in the Chami Mess had to come to a sudden end. One Sunday morning, while we settled the monthly bill with the manager, we were told curtly that the mess was unable to have both of us as regular clients and we should make alternative arrangements. We were given enough hints to understand that the mess was on the losing side because of the unimaginable quantities of food we devoured at every meal. It was only after a long hunt, we found admission to another mess (Subba Rao Mess) on Ajmal Khan Road.

Life fell into a routine. Get ready in the morning, go to the mess, eat lunch and then join the bus queue at Arya Samaj Road to reach office. I found the office interesting. Though I was a photographer attached to the journal, I took part in all the stages of its production. Sheila Dhar, Husaini and Ammu (Alamelu Krishnaswamy) were fine colleagues, very proficient in their work. Sheila was married to P.N. Dhar, who was a professor of economics in the Delhi School of Economics. She was big made but very active and full of life. She was a singer too. But her greatest talent was that she was a good mimic and an excellent storyteller. Husaini belonged to Lucknow, a Syed, shy and serious. He was the son of a well-known Urdu writer. He was lean, tall, scrupulous, and a puritan, a devout Muslim, who prayed five times a day. When he walked in the long office corridor, he gave the impression of a camel trotting. Ammu was much unlike the other two\; short, not lean but compact\; a Tamil lady in a Kancheevaram saree with a red Bindi on her forehead. All the three were gems. A little later, a wiry and a witty gentleman called Srinivasachar (who looked like the great C. Rajagopalachari if he wore dark glasses) joined us. He belonged to Mysore, and had earlier worked with the archaeological department of the State government. He was indeed the Acharya (Guru), a knowledge resource for all of us. He wrote impeccable English and wielded his pen like a calligraphist. Khushwant thus had a very talented group around him, which functioned like a family.

I travelled frequently with them, especially with the Editor, to write and photograph stories on planning and development for the journal. Khushwant loved travelling by train. Both of us were entitled to travel in first class. He felt uncomfortable in the company of strangers and so always preferred a two-berth coupe. He warned me that he snored heavily and that I shouldn't mind. This did not bother me since I went to sleep the moment I stretched myself on the upper berth.

Once I went with Khushwant on an all-India tour\; this time by air. We touched Cochin and stayed a night at the famous Malabar Hotel, ideally located on the backwaters. I had a huge room with teak flooring for myself. That was my first experience of a luxury hotel. I was not entitled to stay in such expensive hotels, but Khushwant was keen that I stayed with him wherever he went. He paid for me. The stay at the Malabar Hotel has firmly stood in my memory because of another reason. When we relaxed on its green lawns in the evening, Khushwant ordered a drink for himself and, at the same time asked for a glass of beer for me. He talked about the much-misunderstood aspects of drinking and persuaded me to try the beer, which I did with much trepidation. That was the first time I had tasted alcohol. Through my life, I never developed a fascination for it but, Khushwant always poured a drink for me whenever I went to his Delhi home. His stay with Yojana was very brief, less than two years. But, I continued with the journal for a longer time and stayed on in the Capital. It was my good luck that I served under very accomplished people.

Wedding Bells

Meanwhile, I began thinking about my marriage. I had always believed that I should marry at the right age and settled down early in life. I was already two years old in my job. I was 25. I wrote to my parents in Mysore about this and wanted them to look for a suitable girl, preferably from Tamil Nadu. I had nothing against Kannada-speaking girls. But, somehow, I felt Tamil girls were smarter, had classical looks and above all they were very photogenic.

Regarding finding a bride for me, my parents discussed the matter with one of my uncles (my mother's brother) who had become some sort of an adviser to them on all important matters. He said that his friend and an office colleague called Krishnan who had a sister named Meenakshi for marriage. The family lived in Madurai. My parents, especially my mother, who hailed from Madurai, jumped at the proposal and wanted him to proceed further with the alliance. Things moved fast.

I received a photograph of the bride for initial approval. In the postcard size black and white photograph, she looked elegant and beautiful with sharp classical features. I put the photograph into a frame and gave it a pride of place on my office table. The picture floored me and my friends. My uncle wrote to me asking for a photograph of me to be given to the girl's parents. He thought that for a professional photographer to produce a flattering portrait of his own was no big deal. It was not so.

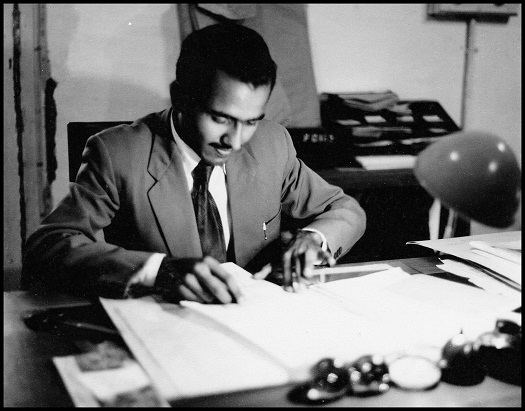

That evening after dinner, my friends and I sat together and went through my collection. None of the pictures made the grade. A fresh picture had to be taken. I discussed the matter with my colleague Sardar Harbans Singh in the office. He felt that it should be a picture showing me as a senior officer, sitting in front of an impressive table covered with green flannel and a table lamp, pin cushion, calling bell etc. on top. Just the way you find senior civil servants in Delhi show off their status. Being a junior gazetted officer, I shared a room with a colleague with the minimum furniture. There was nothing to show off. Finally, we thought of a simple solution. The picture was taken with me sitting in my boss' chair in his room after he had left the office. It was an impressive shot. Years later, I told Khushwant Singh the story and showed him the picture in whose room it had been done. He had a hearty laugh.

I came home on a short leave from Delhi. The boy (me) and the girl (my prospective bride) saw each other (from a comfortable distance, no conversation was permitted) in a cousin's home in Bangalore. The alliance was finalised. The date and place of the wedding was fixed as August 20, 1958 at Madurai. The marriage was a simple unostentatious affair, attended by my Mysore friends. I remember after the ceremony both of us were taken to the temple for a special worship of goddess Meenakshi. It was then I saw the great temple for the first time and the bewitching beauty of the deity in the sanctum with her diamond-studded nose ring which glowed like a blazing star.

I first read an English version of Silappadikaram (The Ankle Bracelet), the great Tamil epic by Prince Ilango Adigal, while I was in college. The poet's description of Madurai, the Pandyan capital, as seen by Kovalan, the hero of the story, captured my imagination. Since then Madurai became special to me. Often I tried to create an image of the city in my mind with its mammoth temple, the celebrated sculpture depicting the wedding of Meenakshi with Shiva as Sundareshwar, its colourful bazaars and above all its women of great beauty, as charming as their counterparts in stone in the temple, with their flowing plaits bedecked with fragrant jasmine. This fascinating picture of the city stayed with me for long and until, I married a fish-eyed nymph named Meenakshi from Madurai making my dream a reality. Madurai no longer remained a poet's fantasy. It became my wife's hometown.

Since I was on a short leave, I returned to Delhi soon after the wedding. I told Meenakshi that she needed to get to know my large family and left her with my parents. She stayed in Mysore at the ‘head office' for a month. My brothers and their wives just loved the pretty addition to the family. My father, who rarely spoke to his daughters-in-law, took a special fascination for the new entrant and conversed with her frequently. My mother took her proudly to her friends' houses in the neighbourhood, almost as an exhibit. The short stay at Mysore without me next to her was somewhat tough for Meenakshi. She had never lived in a large family. She understood not a word of Kannada. Only my mother spoke good Tamil. My father preferred English while talking to Meenakshi. Since their Tamil was bad, the rest spoke to her only in English. She was a hit.

Uncle Ponnu

But I must mention here about an unforgettable incident in the Mysore home, about which she told me in Delhi. This concerned my uncle Ponnu, about whom I have written earlier (available here). One evening, uncle Ponnu came home in a horse-driven Mysore Tanga in an utterly inebriated condition and created a scene, which shocked Meenakshi and embarrassed everyone else, especially my parents. She had not seen anyone drunk. She told herself that she had made her life's biggest blunder in marrying me and become part of a family which possibly consisted of junkies and drunkards. She wondered whether there was any way by which she could erase the wedding and return to her home in Madurai. It took a lot of explaining on my mother's part to convince her daughter-in-law that things were not as bad as she had imagined. Her brother was unfortunately given to the bottle and apart from this indiscretion\; he was a good person, who wouldn't hurt even a fly. She wanted Meenakshi to forget about the incident and not write to her parents. Meenakshi wrote to me that she was counting days to join me without mentioning a word about all that had happened.

Madurai to Delhi was a big change. After a month's stay in Mysore, Meenakshi travelled by air (for the first time) and landed in the Capital to a noisy welcome from my friends. The entire Yojana family was at the airport to receive her. They were stunned by her beauty. She looked like one of those chiselled figurines in the Madurai temple, her skin shining like ebony in the midday sun and eyes those of angels. She appeared as though she had descended from heaven just to taunt the blue-blooded beauties of Delhi. At the arrival lounge, I introduced her to my colleagues and friends. Sheila Dhar was driving us home in her limousine. Ammu sat next to her in front, and both of us at the back. On the way, while talking to me, both Sheila and Ammu lit cigarettes and started smoking. My young wife was in for another shock. She had not seen women smoking. She looked at me in horror and held my hand firmly.

Go to the second story in this sequence.

_______________________________________

© T.S. Nagarajan 2012

Add new comment