Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf

Category:

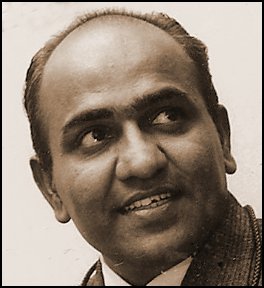

T.S. Nagarajan (b.1932) is a noted photojournalist whose works have been exhibited and published widely in India and abroad. After a stint with the Government of India as Director of the Photo Division in the Ministry of Information, for well over a decade Nagarajan devoted his life to photographing interiors of century-old homes in India, a self-funded project. This foray into what constitutes the Indianness of homes is, perhaps, his major work as a photojournalist.

Editor's note: This story is reproduced, with permission, from Mr. Nagarajan's not-for-sale book of his memories, A Pearl of Water on a Lotus Leaf &\; Other Memories, 2010.

When I think of my father now, in my twilight years, the picture that forms in my mind is one of a thin tall man with no great looks, clumsily dressed, who led a simple life and remained till the end just as God created him.

His cotton suit was never pressed\; shoes never polished\; tie invariably shrivelled, the knot he tied was not bigger than a red cherry. Added to this, he wore a felt hat when he went out to work looking somewhat like a taller version of the great Charlie Chaplin.

He made no attempt to carve out a niche for himself in life except joining the medical school in Bangalore to get a diploma, which made him a doctor, and marrying my mother, a girl of 13\; and with her building a family of an enormous size, and installing her as the matriarch of his home. He gave her all the powers to run his kingdom as his queen and watched her perform from a distance. My mother, on her part, accepted her role with full responsibility and functioned ably trying to balance the large family needs with the meagre resources at her command with much tact and love for everyone.

He joined the Mysore Medical Service as a Sub Assistant Surgeon and served in small towns and villages all over the State, especially in the undeveloped hilly areas on the Western Ghats. His staff consisted of a Compounder (to prepare and dispense the mixtures), a nurse (to dress the wounded) and an all-purpose peon for help. The group functioned as one family. During those days, Malaria was rampant in the State and most of his patients shivered with the disease and many of them died. Quinine, a bitter alkaloid extracted from Cinchona bark, was used as the main therapy for the killer disease. Cholera and plague struck as virulent visitors at regular intervals. Then the hospital functioned as a mobile unit, to conduct mass inoculation camps with the help of additional medical hands who arrived from other places.

The dispensary was everything to him. He was posted as the doctor in charge of dispensaries (now called primary health centres) in small towns like Chkkanayakanahalli, Bannur, Malavalli, Chintamani and in hill towns like Ajjampur and Hunchadakatte, near Shimoga, where I was born. Everywhere he made a name for himself and was popular among the people. He never accepted any money from his patients who got cured, though his steadily growing family needed more cash, in addition to his meagre salary, to run it.

I remember, as a boy of ten, while in Chikkanayakanahalli, during the War, we lived in a house on the main street, close to the dispensary. People, totally unknown to us, came home and left gifts in kind like coconuts, jaggery and fresh vegetables when my father was away at the hospital. Late in the night, emergency cases arrived in bullock carts. My father, getting up from sleep, attended to them, often with my mother to help. One night a man, who had survived a serious attack by a wild bear, was brought home, bleeding profusely from the head. The victim was taken straight to the dispensary accompanied by Thimma, the hospital peon (who had stayed back for the night), carrying a lantern in front, where he was given emergency treatment. The party spent the night in the hospital verandah until arrangements were made to shift the victim to a bigger hospital in the morning.

It occurs to me now that serving the people with dedication was his first priority in life. All else, including the family, came next. He managed to remain all his life like a pearl of water on a lotus leaf. He didn't address himself to any problem and remained at best a mute spectator of all the goings-on in the house. In this endeavour, he got all the cooperation he required from my mother, who performed like a hard-working queen and a trained diplomat. At times when she needed wise counsel, she sought the help of one of her brothers, who was the uncrowned adviser to the family. My father, I am sure, hated his interference, but preferred to remain aloof, just to avoid the prospect of facing the problem himself.

Though the family was unduly large, at one stage with 15 children, my mother worked like an efficient human resources manager. She got a lot of support and help from her own mother who had chosen to live with her daughter after her husband had passed away. We called her "Ammamma" (mother's mother). I can't recall even a single instance when my mother lost her temper on any of us. When the sons got married and daughters-in-law arrived, she treated them on par with her own daughters and solved all differences among them with a unique formula of her own. She praised everyone privately and didn't carry complaints from one to another. She gave each of them the impression that she was the best in her estimation. As boys we quarrelled a lot among ourselves. Whenever we went to her for a judgement, she somehow managed to postpone the hearing until we had forgotten everything and the case had dismissed itself.

She was very fond of her husband and loved serving him like a dutiful wife. When he was away at the dispensary, she functioned like a half-doctor dispensing mixtures from large bottles kept in a shelf at home to women and children who came to her with simple complaints like pain in the abdomen or loose motions etc.

My father, though not a very demanding husband, had his own needs. His major requirement was hot filtered coffee, which he wanted all through the day but only in small doses. Often word came from the dispensary for a flask-full of coffee to entertain friends who came to see my father.

The annual inspection day by the DMO (District Medical Officer), his boss, was very special. It was a busy day for mother who had to send parcels containing Masala Dosas and coffee to the hospital for the VIP's breakfast and later cook an extraordinary lunch. When the time came in the evening for the DMO to depart, Thimma, the peon, had instructions to keep the VIP's Ford loaded with coconuts, jaggery, jack fruits and what have you.

My father kept good health but suffered from headaches frequently. When he came home after a tiring day at the dispensary, he wanted his coffee followed by an "oil bath" to get rid of his nagging headache. In fact, the oil baths were a regular feature in the house. On every Saturday evening, father used to smear his entire body with Castor oil and after waiting for a while to let the oil enter his skin, would follow it up with a very hot bath using Shikakai (soapnut powder) to get rid of the oil. There were no Shampoos then. This regimen applied to us boys too. We hated the slimy ritual every week, but it was unavoidable.

Meal time was like a military exercise. All of us sat in front of banana leaves spread on the floor in a line with father at the head. The eldest sat next to the father and the youngest at the end. No talking was allowed except for asking for an extra helping, not loudly. Father ate his food slowly. Some of us were fast eaters. We had to wait until father finished and got up. But what was special about the meal time was that when it came to mother's turn to eat, she sat in front of the same leaf which father had used earlier and ate her food from it, served by one of the daughters or the daughters-in-law. This was the custom generally followed in Brahmin homes. Years later, I found a somewhat convincing explanation for this bizarre custom. In large joint families there were days when some dishes got exhausted by the time the women's turn came to eat. To make sure that the wife got a particular dish, the husband made it a point to leave a portion of the dish unfinished on the leaf to make sure that his wife, who followed him, tasted it.

He loved his evening walks with friends like the veterinary doctor, the sub inspector, and the Amildar (Revenue Officer) of the place. There were days when he carried a handful of ground nuts in his coat pocket to munch as he walked. Returning home after the walk, before the street lights came on, all that he did was to sit in a chair in the verandah and watch silently whatever was happening at home.

He talked less, especially with us children. I had never seen him read a book\; but he read the day's newspaper religiously before going to work in the morning. He wrote very legibly and used only post cards for his correspondence. He opened postal covers with meticulous care, cutting at one end with a pair of scissors. Then he used to blow air into the envelop through the open end to look in and make sure nothing else remained inside after the letter had been removed.

He never went to see movies and hated film music. In fact, he never appreciated or understood any music or art of any sort. He was not a much travelled man. I wonder whether he had ever gone outside the State, even as far as Madras. His only transport was a bicycle. He bicycled in the morning to see his friend even on the day he passed away.

He remained a smoker all his life. His preferred brand was Gold Flake, then a costly brand in yellow packets. When at home, he managed to smoke clandestinely somewhere in a corner in the compound but never in front of his children. When I lived with him in Malavalli, going to school and cooking food (the rest of the family remained in Mysore), I could observe my father closely. We slept in the same room\; he on a cot and I on the floor. Lying on his bed, he waited till I slept to light his after-dinner cigarette. Sometimes, I pretended as though I was asleep and waited to see the little red glow at the tip of his cigarette in the dark. After retirement, he gave up buying cigarettes in packs of ten and bought one cigarette at a time, perhaps because he could no longer afford the luxury. He was punctual to the minute though he never wore a watch. He hated people given to the bottle. His only luxury was buying lottery tickets occasionally but never won a prize. He spoke adulterated Tamil at home but when he was angry his language was English.

At no stage in our school-going life, we were pressurised by the parents to study and perform well in the examinations. At the start of the academic year, father took us to a tailor and got our dresses stitched. Mother made sure that all the text books we required were bought. Even during examination time none of us was asked whether we had done well. It was assumed that we would do well, always. Most of us passed with distinction while one or two found it difficult to rise above the average grades. But almost all of us carved out careers for ourselves and did well in life.

After his retirement, because of his very meagre pension, father expected his sons to take up jobs soon after their education finished and help the family with additional funds. I graduated with a B.Sc. degree from a college in Mysore. My father was keen that I take up the job of a high school teacher. In fact, he went to the extent of making me write out an application, much against my will, for the job of a teacher addressed to the Chairman of a school management, who happened to be his friend. I hated becoming a teacher. My thoughts were focussed by that time on photography and journalism. My father didn't like this at all. He thought it was foolish on my part to try to do what my eldest brother Satyan had successfully done. After kicking his job of a teacher in a Mysore school, he had taken to news photography and had joined the "Deccan Herald" in Bangalore as its staff photographer.

One day a letter from the school arrived calling me for an interview. I went to the interview wearing a coat borrowed from a friend. There were many applicants like me for the job. When my turn came, I was called in and asked to sit facing a group of old men in which I could identify only the chairman, who was my father's friend. The panel found me suitable for the job of an English teacher, though I was a science graduate. The chairman, to my utter surprise, told me of my selection and wanted me to take up the job as soon as possible. This was a decisive moment for me. I thought for a while and told the chairman bluntly that I had taken the interview just to please my father and that I did not want the job because I had decided to become a photographer and a journalist. After requesting him to please forgive me, I got up and quietly walked out of the room.

The prospect of facing the father at home frightened me. I spent the rest of the day with friends and went home late in the evening. The main door was opened and I found my father sitting in his chair and talking to a friend. As I went in with my head down, quietly walking past them, I heard my father telling the friend "This is my son about whom I was talking. He threw up a good job this morning," and followed it up with some adverse comments about me and my misplaced goal in life. I felt relieved that the news had already reached him and I had been spared from the difficult job of reporting it myself. I went straight to my mother, told her everything, packed my personal effects in a bag, went out through the back door, jumped the compound and walked towards my brother Satyan's house. He lived with his wife and son separately in a rented little cottage in the same locality.

I continued staying with the brother for the next one year, assisting him in his photographic jaunts. One day I noticed an advertisement in the newspaper by the Union Public Service Commission for a job of a Photographic Officer with the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting in Delhi. I promptly applied for the job and forgot all about it. Months later, a telegram arrived, asking me to appear before the Commission for an interview. I travelled to the Capital by the Janatha Express (the cheapest among the available trains to Delhi from Madras), stayed with a friend of my brother, and appeared for the interview.

This time I was keen on the job. There were many applicants from all parts of the country. I did my best and at the end of my interview I was told by the chairman of the selection committee that I had been selected and that they had decided to start me on a higher pay in view of my excellent performance. The first thing I did after the interview was to send a long telegram to my father giving him the good news.

Years later when I heard that my father had suffered a paralytic stroke and survived, I went home on a month's leave to be with him. He had recovered well and was even able to walk. His speech had not been affected. I took him out for short walks every evening and was with him all the time trying to comfort him. One day, as we walked, to my utter surprise, father referred to my success with my career and bluntly apologised for what he had said after I had declined the job of a teacher. I didn't know what to say. When I looked at him, I found my father struggling to hold back his tears. Five years later, I went home again. My father had died of a second stroke. This time it was my turn to hold back the tears.

© T.S. Nagarajan 2010

Add new comment