Chapter 12: Premature birth, typhoon and typhoid

Category:

Tags:

Visalam Balasubramanian was born in Pollachi, on May 17, 1925. She was the second of three children. Having lost her mother at about age 2, she grew up with her siblings, cared for by her father who lived out his life as a widower in Erode. She was married in 1939. Her adult life revolved entirely around her husband and four children. She was a gifted vocalist in the Carnatic tradition, and very well read. Visalam passed away on February 20, 2005.

Editor's note: This is Part 12 of her memoirs, which have been edited for this website. Kamakshi Balasubramanian, her daughter, has added some parenthetical explanatory notes in italics.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9 Part 10 Part 11

I had problems when I conceived Radha. Even now I wonder how Radha grew up to be a formed baby and how she was normal in all faculties. Every once in a while there was 'threatened' abortion. And no doctor told me to go to bed or take rest at such times. During a routine ante-natal check-up, Dr. Mukadam felt I was weak/anaemic. She decided to give me a boost, and prescribed a course of six injections. Second and third injections I got rashes like urticaria and stomach cramps. We did not report these to any doctor. The fourth injection was on the day prior to Vinayaka Chaturthi (Festival in honour of Lord Ganesha. Occurs usually in mid -September-KB).

We were awaiting a male cook to come from Tirukkarugavur a week later. My father had already sent a Nayar woman to work for us. There were two others working for us. But I didn't have the ability, forethought to coordinate their time and work to the best advantage, though they were sincere and willing workers.

Thus, one day, the old man, Maharaj had gone home after the children had had their lunch. Padmavathy was out gathering cow dung to dry as fuel for the hot water boiler. She did it on her own. Papu and Ramesh were at the neighbour's.

I began making preparations for the pooja next day: grinding, pounding, etc. I felt a catch in my lower abdomen on the right side. I thought I had sat in a wrong position, but found I couldn't change position, stretch my leg, nothing. The front and back doors were closed. I called out to our neighbour, because I needed someone to come and help me.

The two adjoining open yards where I was sitting had only a separating wall about 8 feet high. Had there been a man in that house then, he would have jumped over as there were convenient niches to serve as foothold. But that mami ("Mami" is a form of address and title by which older ladies are referred to in Tamil in certain communities--KB) couldn't do so. She came to the trellis door at the front, and I just managed to throw the key to her. She knew I was pregnant. So, she sort of dragged me on to a sheet and fed me hot rasam satham (Rice mashed with thin, spicy lentil soup, a dish much loved by most Tamils and eaten virtually at every meal, including in sickness-KB).

Poor lady. She thought a little warm fomentation will help, and that probably did something contrary. My placenta got ruptured or something. I began to bleed but didn't know it to be so. She caught hold of a passer-by, got someone to send word to TVB at his office. Dr. Mukadam, who was looking after me, came and prescribed a course of 30 injections to stop the process. She was going to be on leave as her father was ill.

By evening my condition held and another lady doctor, equally renowned and capable, was called in just so that in case of need she could attend to me and I might go to the hospital where she was working. I was such a fool that I was talking pointlessly about how well organised I had been with baby clothes, change of dress for me, rolls of cotton wool packed tidily before the birth of Ramesh and Papu. She said, "This is not the time to talk about baby clothes. We can get all those readied quickly."

Then I began bragging about how sensible and methodical we were by registering with a doctor and going for regular check-ups. Here I mentioned Dr. Mukadam's name a number of times. It must have interfered with her examination of me and irritated her. Reluctant but annoyed she withdrew saying that she won't impose herself if I preferred Mukadam. I hastily changed my tune. She told TVB that getting me to a hospital was the sensible thing to do. TVB decided to bring the second in command at Lady Elgin hospital where I had registered. She advised not moving me just then.

Next day, however, I had to be shifted to the hospital by ambulance.

Our neighbours, Mr. and Mrs. Nataraja Aiyar had been there for nearly a year or so. My children were always - all the time - in their house. Their son, then 20 or so, eldest daughter, 17 I guess, and youngest just turning 15 were in Nagpur studying. Nataraja Aiyar's stepmother was there keeping house for them. That lady's only son, Nataraja Aiyar's half-brother was with Mr. and Mrs. Nataraja Aiyar, studying in college at Jabalpur. As my children were used to spending all their time in their house, they had no problem whatsoever when I was away in the hospital. There was a family of south Indian Christians living in the house opposite. They were a friendly family. Pious Christians. Mrs. Gonzolvez accompanied me to the hospital. Mr. RCR (Sri. R. C. Ramakrishnan, who happened to be TVB's colleague at work) took Ramesh to his house. Papu was with Sri. Nataraja Aiyar. Savithri stayed at home with TVB.

Meanwhile, cook Cheenu had been summoned and was arriving the next day.

On the evening of my entering hospital, my labour started. TVB had gone home for the night and the maid Padmavathy was there. The hospital staff moved me to the labour ward. For all the education I had had and the experience, there cannot have been another fool like me. I never realised the gravity of the situation. I was only into my seventh month. There was not much of an assurance of a safe delivery of the child, of the child being able to survive, and me coming out without any possible damage. All I was worried about and demanding was that the senior doctor should deliver the baby. The staff nurse and the matron tried their BEST to persuade me and convince me. For not less than three hours I bore the pain, struggled with them, quarrelled and finally made the doctor come.

By my stupidity and obstinacy, I might have killed my child, damaged her brain. But GOD, THE SUPREME BEING watched over my unborn baby. She was safely born.

As a premature baby she had to be taken care of differently. Shutting out sunlight and fresh air because her outer skin had not formed, and she didn't have eyelashes, eyebrows or hair on her head. For a few weeks, we had to feed her milk only through a pipette. Even so she developed some kind of anaemia. The doctor drew out blood from me and injected it into her, three times before leaving the hospital.

Massaging warm olive oil with a piece of cotton wool, we had to keep her wrapped in wads of cotton wool. She looked completely bandaged. Only her face and bottom were not wrapped up like that. She was kept in a darkened room under a mosquito net which in turn was covered by cloth on all sides. Massaging her was very tiring because her limbs were tiny and too delicate.

Every morning as I was half-way through the massage, our cook Cheenu used to give me something warm to drink and would suggest that I take a little rest before doing the other limbs. It was he who thought of placing a cup of oil in warm water on a low fire on a charcoal stove so that the temperature was maintained. Such a kind and thoughtful man!

Anyway, she grew up to be a happy, nice-looking child but not before she contracted all the illnesses that were going round in Jabalpur.

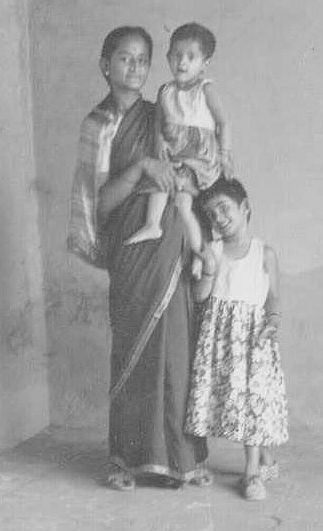

Visalam with Radha and Papu, Jabalpur 1952

Actually on the day I was discharged from the hospital, Dr. Mukadam told me to look at the child first thing in the morning and tell myself, "This is not my child," because she would be the first to catch any infection from miles away. As a matter of fact, it was from her that TVB caught his typhoid. By then she had crossed two years of age, and TVB got transferred to Madras.

***

While in Bombay (1947-49?) TVB didn't keep good health. He was much troubled with wheezing, which was diagnosed as easonophilia. The diagnosis and treatment were not done in the early stages because it was thought the rainy season of Bombay and the dust and smoke from the cotton mills as well as the train were causing congestion in the throat. Here again I must confess I wasn't aware of the extent of his suffering or illness. I was a dunce. He also had a biggish boil on one of his toes making wearing shoes and socks quite painful. That boil didn't subside till he was cured of easonophilia.

The climate in Bombay was not conducive, either. A cyclone of frightening magnitude hit Bombay unseasonally in 1948 soon after Papu was born. Ten days after her birth. Our place of residence was a rickety structure. Constructed during the War. Our house was the first in a row of houses, thus standing right out. Roof on the kitchen and latrine flew away first, and then the doors from the backyard and latrine just broke away from the hinges. Roofs on the other parts of the house were swaying threateningly.

My mother-in-law and Subramanian (a cook) were holding the children Savithri and Ramesh with wide cane chairs around them as shields. I was bending over Papu whenever a gust of wind hit with force. Trains were disrupted owing to water logging (Then, as indeed now, electric trains are the most convenient mode of local transport in Bombay--KB) But TVB managed to get home before we could even begin to worry. He caught hold of trucks and buses passing his way and reached home.

Similarly, once it rained so heavily and continuously in Jabalpur that embankments of some railway tracks collapsed, and several areas got flooded with water up to 10 to 12 feet, which submerged huts. It had been raining since the previous evening. Anticipating inundation, batches of trainees from the training centre where TVB was working came around early in the morning and lifted up all the things like suitcases, sacks of food grains and whatever else had to be kept out of reach of the rising waters, to the top shelves.

By 10 a.m. the water level was at least 7 feet high inside our house. Friends suggested that the children be moved to RCR's house which was on a higher level as well as away from the broken embankment. But TVB said that all of us will stay together. He stacked a few wooden packing cases one on top of another, anchoring them safely, using wooden frames and put all the four children there. We climbed on raised chairs and tables, and sat through till the water receded by about 3 p.m. It must be said to the credit of our children they did not ask for a proper meal. Snacks and water which I had the forethought to keep available were all they had.

As I said earlier, we had three servants working for us\; TVB's contention being that in case one was absent there will be another available to help out.

And true to his argument, Dal Chand, who lived farthest away of the three, and one who held a job in a factory turned up shortly after the waters receded. (The other two were Maharaj and Jumni Lal. Maharaj was a resident cook in a house nearby. He came twice - morning and evening - to our house to pump water at the hand operated ground water bore pump in our courtyard and take out the children for a stroll. Jumni Lal worked in several houses, washing, scrubbing and cleaning, whereas Dal Chand worked in a factory, helped in our kitchen in the evenings.)

That evening, cleaning up was no easy job. There was clay, mired with dead rodents, fish, loose weeds, et al, scattered all over the floor. Even the water pumped out came muddy. Dal Chand came fully prepared to clean up the house for us.

It was the aftermath of that dirty water, soaked into the walls, smell of mud everywhere in that area, that brought on typhoid. First Radha, the prematurely born child, and next, TVB.

***

We lived in Jabalpur for four years.

Visalam, 24, homemaker and mother of three. Radha was yet to arrive. Jabalpur, 1949.

Savithri always had problems with enlarged tonsils. She developed mastoidal catarrh. She was hospitalised and given three-hourly penicillin injections. The following week (while her body had been cleared of infection with such continuous, big doses of penicillin!) the senior most surgeon took out her tonsils. She had always breathed through her nose, and also ate with her mouth closed. Now, after tonsillectomy, I saw she breathed through her mouth, and she was just unable to draw air through her nose. I mentioned it to TVB and the doctors. They said she will get back her habit and now she was perhaps feeling sore in the throat region. Even after a week she couldn't draw breath through her nose. But the doctor didn't pay any attention to it, and TVB also said I was fussing. Thus it was never remedied.

The first house where we stayed in Jabalpur was not in good condition. And since it was the rainy season then, the house used to be crawling with earthworms. Papu was then moving around on all fours (crawling too!). Like all babies she would catch, crush ants and earthworms, and put them in her mouth. Maybe because of that she developed a bad stomach problem. Digestion got spoilt. Vomited food. Refused bottle. Luckily it was my milk that saved her because that was the only food she would have and could retain. But it was not enough. I remember crying one day that we might not get her to grow well. In spite of her hunger and poor health she used to be laughing and playing with Savithri (5 1/2) and Ramesh (2 1/2). TVB took her to Dr. Mukadam, who diagnosed her problem, prescribed proper medicines and food.

TVB's typhoid was just as bad as Savithri's and Radha's. The fever relapsing once, twice, was the way in Jabalpur. All of our friends helped with everything. The trainees were always there in the night. Giving medicines, taking and recording his temperature, changing clothes on time, the sheets and the pillow. They were there ready to assist me.

During the relapse, doctors advised hospitalisation. At that time, one of TVB's colleagues, Mr. R. Radhakrishna Aiyar wrote to my father-in-law suggesting that TVB's mother had better come. Sri. R.R. (i.e., R. Radhakrishna Aiyar) believed a mother will be anxious and would come. He did not know my father-in-law and mother-in-law. On learning of TVB's fever, my father had sent his cook and clerk from his bank--Venkatesa Iyer and Sadasivan respectively. My father-in-law was not very pleased that assistance had come to me from Erode, my parents' home.

My father-in-law would talk of emotion and feelings only when it suited him, and talk of practicalities and pragmatism again to suit his actions.

But then my mother-in-law herself may not have been over anxious to do the journey, etc. and she certainly would not have been helpful. She knew how to be helpful and could be helpful too. But she would do that willingly, to help a daughter. When she was made to be of help to a daughter-in-law, she would do everything very well, but she would hurt and wound the daughter-in-law with words.

My father-in-law sent "Narayanan and Gowri" (I am using his words) to Jabalpur, and wrote in reply to Sri. R. R. explaining his views. Seeing that a cook was there already who was also an able bodied man, he'd much rather send these two because they are practical thinkers and not TVB's mother who is old, etc.

My brother made a couple of trips to Jabalpur when TVB was ill. On his way back, he looked up my father-in-law to report on TVB's condition/progress. My father-in-law gave vent to his feelings. He told my brother that I had not cared to write to him but chose only to keep my father informed. (I was not in the habit of writing to him nor receiving letters from him.) Request for assistance was never made to him. It was Sri. R.R. who thought of the mother (old parents) and it never occurred to me that TVB's mother would be worried. My brother reportedly said to my father-in-law that if only accusing me for failures was his concern and not learning about his son's condition, he would go away. (This my brother told me.)

With my brother-in-law Narayanan and sister-in-law Gowri, Sadasivan and Venkatesa Iyer and our own servants, Maharaj, Dal Chand and Jumni Lal, there was no problem at all in running the house, sending the children to school, bringing them back, going back and forth to the hospital.

My father was sending me money also, though it was not needed. Returning the money to him would be discourteous, so TVB made gold ornaments for my brother's wife, making it a gift because he wouldn't accept anything from my father for himself. My father was so worried and worked up - more so because he could not come personally - that his health got affected. He had arranged for several kinds of poojas in temples in Erode\; I was told he used to go and sit through all of it. The dark, tiny places near the sanctum sanctorum, heat, lack of ventilation, and his own age (he was 61) told upon his health.

Often when I think of my father, I feel very bad because we let him down. We three. We three children for whom he lived. He had no other interest in life. We were everything for him. He loved us much, much more than we deserved. And, all of it was wasted. There was nothing we did to make him happy. If he derived any pleasure from anyone of us at any time, it was a result of what he had done for us. If he enjoyed my singing, it was because he had taught me through excellent teachers, and gave me a lot of opportunities to listen to good music. On the contrary, every one of us shared a part in breaking his heart. I broke his heart, because my husband treated him like an enemy and shunned him.

We are unable to judge the course of destiny in anybody's life. Nor are we able to learn anything from our own guidance. Our experiences, our memories, and our own contribution to the world we live in are as transient as our living/sojourn on earth.

____________________________________________________

© Kamakshi Balasubramanian 2016

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people\; the comments must be related to the story. The purpose of the approval process is to prevent unwanted comments, inserted by software robots, which have nothing to do with the story.

Add new comment