Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

Memories of Life in Sindh and the Migration to India

Category:

Tags:

Sunder Ramchandani was born in Sindh and migrated to Delhi in late 1947 with his family when he was 9 years old. Upon receiving his Bachelor's degree, he devoted a lifetime to a career in the Indian Airlines Corporation. He retired as Deputy General Manager of Flight Operations in 1999 and now lives in Hyderabad, Telangana with his wife, son, and daughter-in-law, and two granddaughters.

Dilip Ramchandani was born in Delhi, the oldest of three children, to the late Indersingh and Ranjana Ramchandani. He graduated from the Maulana Azad Medical College in Delhi and, after emigrating to the US, trained in psychiatry. He retired two years ago from the Drexel University College of Medicine and now divides his time between Philadelphia and Washington DC. He and his wife, Parvati, a uroradiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, spend time with their two daughters and their families that include a granddaughter and a grandson.

Editor's note: Dilip reached out to his uncle, Sunder, to write this story. It is based upon a loose compilation of the memories that emerged in their recent telephone conversations and some notes and photographs that Sunder was able to provide.

Our family's story

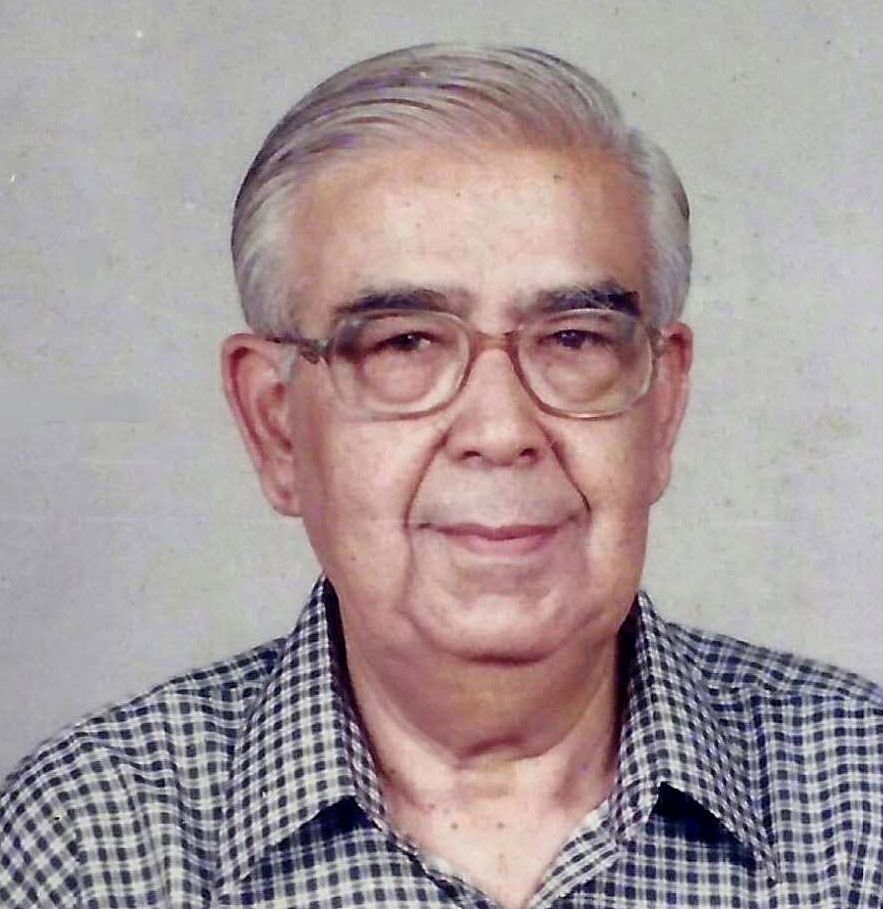

I grew up in an extended family. My grandfather, Utamchand (we called him Baba), died at home in 1954 when I was three years old. After he passed away, our family consisted of my grandmother, my father, the oldest of 4 siblings, including Sunder, my mother, and my two younger siblings. The displacement from Sindh and its inevitable trauma was a low hum in the life of my family. Frequent conversations about their lives in Sindh were a staple of our family, and Sindhi was our spoken language at home. Sindhi was written in the Arabic script in Sindh. Although recognized in British Sindh, the Devanagari script did not find much usage until the 1950s in India.

Uttamchand Ramchandani ("Baba"). Dilip's grandfather, Sunder's father. Delhi. 1953.

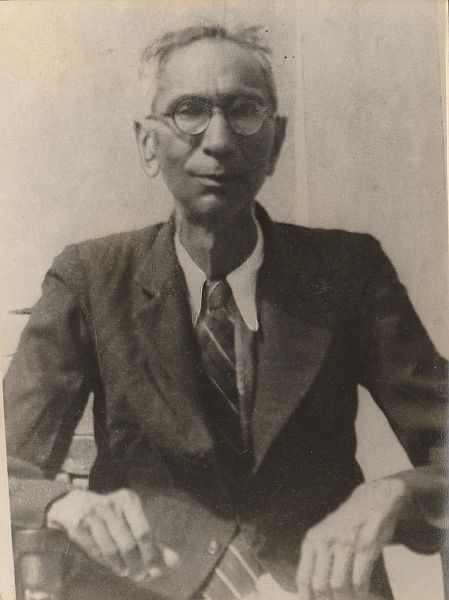

My grandmother, Dayali (we addressed her as Bhabhi), was the fourth wife of Baba, who was twice her age. His first three wives had died successively during childbirth. She gave birth to my father, Indersingh (the firstborn in our family was given a Sikh name) but could not get pregnant for several years after that. My uncle, Sunder, was born thirteen years later, in 1938, reportedly after 'purification' of her blood by leech application. Then, two more children were born in quick succession: Prem, a son in 1942, and Gopi, a daughter, in 1945.

Dayali Ramchandani ("Bhabhi"). Dilip's grandmother, Sunder's mother. Baroda. 1990.

The family lived in the Ramchandani Ghitti (street) of Bhurgri in Khairpur district until 1942. That year, my father graduated from high school. To allow him to continue his education in college, the family moved to Karachi, as was the custom for families seeking higher education for their children. Karachi was an overnight train journey away from Khairpur. So, they left behind their haveli in Bhurgri in 1942 and rented a flat in the Metharam Thakurdas Building on Burns Road in Karachi. It was a second-floor corner flat on the street that led to Burns Garden and consisted of many buildings with residential flats on the first and second floors.

The ground floors were occupied by shops and small businesses. Dr. Kalyan Das's clinic was on the ground floor of my family's flat. However, Baba did not trust his medical acumen, so the family sought out a different doctor.

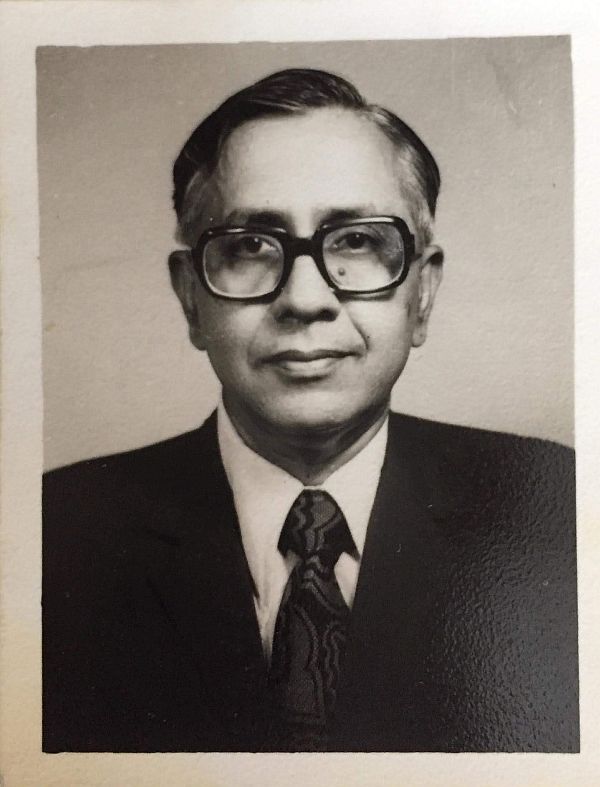

After my father received his bachelor's degree in Economics, he taught at a local school, returning home every afternoon with his clothes profusely coated with chalk dust. He was toying with the idea of finding a better paying job with the Government of India in Delhi. To that end, he applied and received an invitation for a job interview in late 1946.

Baba was very protective of his children, and particularly his oldest son, Inder. So, Baba accompanied my father for his job interview to Delhi. From Karachi, they boarded a train to Lahore and on to Delhi. It may have taken two or three days for the journey. It would be several months before he would hear of the outcome of his application.

By 1946, it was clear that the British would leave. There was little appetite and few resources in war-depleted Britain to maintain an empire. A tentative departure date of June 1948 had been set, but there was no agreement in sight between the Congress and the Muslim League about what the independent country would look like.

Most Hindu Sindhis did not desire to leave Sindh. The prevalent opinion was to stay on in Sindh after independence. Although it had been ruled by Muslim rulers for hundreds of years and by Muslim administrators during the Bombay Presidency since the mid-19th century, the majority Sindhi Muslim population got along amicably with the minority Sindhi Hindus, albeit on a business level. The last Hindu Sindhi King, Raja Dahir, may have ruled in as early as the 8th century.

The Ramchandani family traced its origin to roots in Jaisalmer. Hingoromal left Jaisalmer in 1759 and his successors eventually found their way to Khairpur via Khudabad and Hyderabad (Sindh). One of his grandsons was Diwan Ramchand, whose descendants adopted the surname Ramchandani. Members of the family were identified as Khudabadi Amils (Persian for "educated").

Baba passed his high school examination, for which he had to travel to Bombay before WW I. He was an army contractor who profited during the war. Being deeply superstitious, he began to believe that his long struggle in achieving fatherhood was a punishment for sins of commission or omission that he may have been guilty of as the owner of a profit-driven business. So, as penance, he gave it up and lived off his savings and land holdings for the rest of his life. He was convinced that he was amply rewarded by the birth of my father and, subsequently, three more children!

In 1947, Sunder was only 9 years old and in the 2nd "ENGLISH" grade. The high school curriculum in Sindh was spread over four "SINDHI" grades followed by seven "ENGLISH" grades. He had some friends in the neighborhood. A Marathi family had lived across the street for many years and spoke fluent Sindhi. Their son, Shivaji, was one of his friends. As a treat, Sunder would walk to the corner Irani store that sold delicious maska buns.

News of independence of the country continued to gather steam, and schools would close off and on that spring, as a precaution against civil disturbances. Tabloids, sparse radio broadcasts, and word of mouth were the primary sources. Sunder was privy to his older brother and father huddling together to discuss options but unaware of the content. Occasionally, he would accompany Baba to local meetings of the Muslim League and the Congress party. The community was generally peaceful and he did not observe any incidents of violence or looting as days went by.

The first inkling of the turmoil that lay ahead came after a political meeting that Sunder attended with Baba. An Urdu speaker exhorted the Hindus to leave Sindh - "Yeh Mulk Hamara Hai, Hindu Chale Jao (This is our country. Hindus should leave)". Yet, he does not recall any impending family-talk of plans to leave Karachi or Sindh.

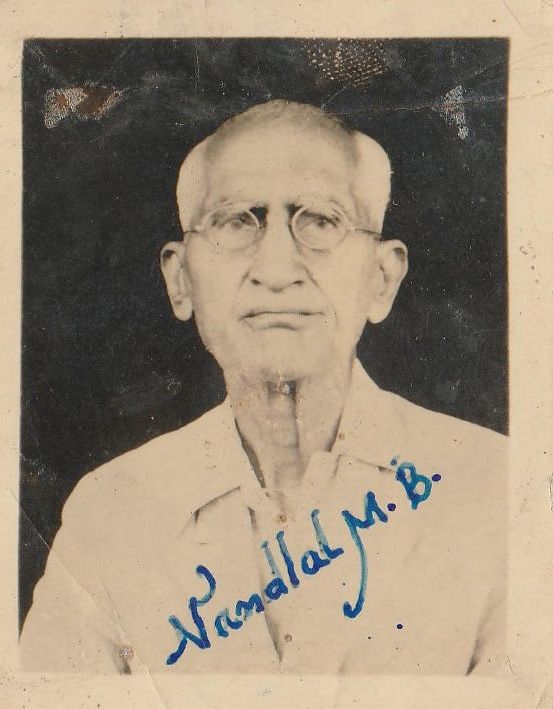

As spring led to the summer of 1947, Sunder wanted to visit his maternal grandparents in Khairpur. Kako Nandlal (and his wife, Putlibai) was a prosperous, and intimidating, farmer-landlord, who lived in Khairpur but owned farmland in Nawabshah, about 10-15 miles away. Nandlal had a compound of 3 homes, one each occupied by his family, his older son, Daulat's family and his late son, Hiranand's, family. Sunder was anxious to visit them as he had many cousins of his age to play with in his grandparents' home.

Kako Nandlal. Dayali's father, Sunder's maternal grandfather, Dilip's great-grandfather, Kalyan Camp, Bombay. 1948.

The custom was to buy a ticket and take your child to the railway station. One would invariably find an acquaintance traveling to Khairpur who was trusted with the custody of the child, who would be received by a family member at the other end. So, Sunder took off as August 14 loomed.

Lord Mountbatten had arrived as the last Viceroy of British India in the spring and things suddenly took an unexpected turn. In June 1947, he made a decision to advance the British departure to August 1947, and to divide the country into India and Pakistan.

Sunder was with his grandparents at the dawn of Independence but does not recall a sense of shared exhilaration, since news was sparse and he was content playing with his many cousins. He does remember that his maternal grandfather took him to visit the Ramchandani family home in Bhurgri that he had left at the age of 4 and recalls that a supporting wall had caved and needed to be rebuilt. When informed by Nandlal, Baba was so discouraged by the receding prospects of ever returning home that he did not see a reason to do the needed repairs.

In late August 1947, a post card arrived from Karachi. My father had received an employment offer from Delhi. This spurred the family to decide to leave for India. Nandlal was asked to make arrangements for Sunder's return to Karachi. The overnight train to Karachi from Khairpur made a halfway halt in Hyderabad.

There were reports of commotion, violence, and looting in Hyderabad. So Nandlal could not convince any of his employees to chaperone Sunder to Karachi. Finally, Baba persuaded a cousin, Sobhraj, who was an influential man who lived in Sukkur, 10-12 miles away, to use his connections to arrange for Sunder to return.

Sobhraj was able to persuade two Sindhi Muslim army officers to escort Sunder to Karachi. An attendant came to pick up Sunder from Khairpur to Sukkur in a tonga (horse driven carriage). Sunder remembers the famous Lansdowne Bridge that spanned across the Indus River on the way from Khairpur to Sukkur as being devoid of people or traffic - an expanse of eerie emptiness! The bridge had been built in the late 1800's and was a major connecting link between Sindh and Punjab provinces.

After a brief stay in Sukkur, Sunder boarded a second-class compartment in the company of the two officers. He slept on the upper berth and the officers occupied the lower berth. At the Hyderabad station, there was banging on the doors, crowds wanting to be let in, but the officers kept themselves and Sunder locked in. They got off the train, not in Karachi, but at the Drig Road station, one stop short of the main station. Here, they hired a Victoria coach to safely deliver Sunder to his family!

The month of October 1947 was hectic for the family preparing to leave their home and city for good. Pathans from Baluchistan arrived in droves to buy goods that the relatively prosperous Hindu Sindhi families were trying to get rid of in preparation for their departure. As the Pathans scoured the neighborhood, Baba negotiated the sale of belongings - furniture and such. The family packed their clothes in steel suitcases, with kitchen pots and pans in a gunny sack.

Finally, in early November 1947, the family boarded a steamship at the Karachi Bundar (port). The long journey to Bombay took several days in the steamship that had 12 cabins and a deck. Directly from the Bombay docks to the Victoria Terminus, on board the Dehradun Express in a compartment marked "Reserved for Refugees", the family made the last leg of their journey to Dehradun. Here they stayed temporarily with a relative who was a Forest officer.

My father got off the train in Delhi to report for employment. A month later, his parents, two brothers and their 2-year old sister were reunited with him in the Lodi Colony tenements that had been constructed to receive displaced people from across the border.

Indersingh Ramchandani. Dilip's father, Sunder's older brother. Delhi.1970.

Sindh became a walled-off wound that never healed.

Another family's story

Jhamatrai left Hyderabad (Sindh) with his wife and their 8-year old only son, Hardas, on the train to Ajmer. The train was attacked and, in the melee, Hardas was separated. The train moved on and the child was nowhere to be found. The distraught couple was helplessly heartbroken in their tragedy and their efforts through bureaucratic channels came to a naught.

Many years later, Hardas, now Hamid Khan, traced his lost parents in Bairagarh Sindhi Township in Bhopal from a news item that he found in a Hyderabad (Sindh) newspaper. During a Muslim Festival in Bhopal, the Indian Government allowed some Pakistani citizens to visit. So, Hamid took the opportunity to come and visit his family.

After he had been lost, a kind Sindhi Muslim family had found him and raised him as their Muslim adopted son. He was well-settled and married. Jhamatrai and his family were overjoyed but accepted Hamid's decision to return home to Sindh.

Epilogue

In the 1980s, there was a brief detente between India and Pakistan when Rajiv Gandhi and Benazir Bhutto ascended to leadership. It was possible to get a visitor's visa to travel to Sindh. My father had talked often about visiting his lost homeland and, at last, it seemed possible. My father and I began to make plans to travel. However, at the last minute, my father lost heart and could not bring himself to go. Sindh would remain an undigested memory.

_______________________________________

© Sunder Ramchandani and Dilip Ramchandani. Published October 2019

Comments

Family Tree

Sobhraj Ramchandani

Add new comment