Journey Across India, 1950

Category:

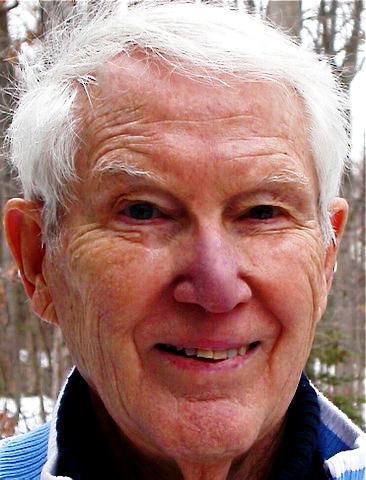

John, born 1926 in the U.S., got his Ph.D. from the London School of Economics after studying at Yale and Northwestern universities. He lived and worked in Samoa, Laos, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Philippines, and Thailand for various U.S. development agencies and foundations, was a visiting scholar at MIT, Harvard and the East-West Center, served as U.S. Member of the South Pacific Research Council, on several boards and undertook consultancies for the Aga Khan Foundation and international agencies until he retired in 2000. He lives with his wife, Catharine, near Washington, D.C.

![]() Six decades after the fact it has not been easy to write this memoir recalling my early impressions of India. I have tried to present an accurate account of the places, people, and events as I remember them.

Six decades after the fact it has not been easy to write this memoir recalling my early impressions of India. I have tried to present an accurate account of the places, people, and events as I remember them.

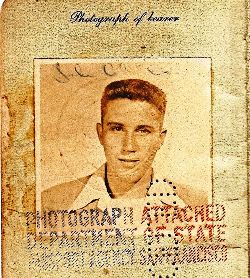

At twenty-three, I was a product of America's Great Depression, of a year at Yale, of the Navy and of WWII. I was of that generation of optimistic post-war Americans who believed all problems had solutions and that mankind was poised to achieve a more equitable and peaceful international order. We could, if we chose, improve the human condition by creatively applying the intellect, resources and talents that were within our reach and, at a personal level, it was our obligation to attempt to do so. Such views shaped my lenses and outlook.

After my years in the Navy (1943-1947), I had helped establish the first High School in American Samoa at Pago Pago (1947-1949). In mid-1949 I decided to leave teaching and to make the ‘Grand Tour' around the world before undertaking graduate study. I sailed via Tonga and Fiji to New Zealand and Australia, working for a time in the goldfields at Kalgoorlie in Western Australia then moving on to run a tin dredge near Kuala Lumpur in Malaya.

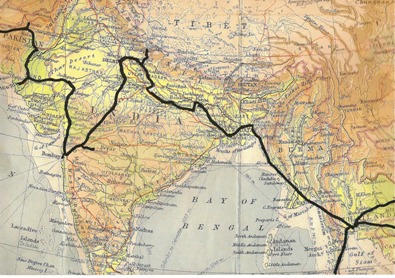

My Indian odyssey began in my mind as I searched for a route to travel from Malaya to London, where I had been accepted for graduate studies. Proceeding overland appeared to be an inexpensive option but was, I was told, fraught with difficulties and possibly with dangers. Sub-consciously my design may have been to follow in the footsteps of my Grandfather who had, as a young man in the 1880s, served three years with the Asiatic Squadron of the U.S. Navy on ‘China Station' and subsequently circled the globe. Despite much cautionary admonishment, the road and rail maps indicated that an overland route was possible and would carry me across India.

In early 1950 I left tin dredging to visit Cambodia to visit Angkor Wat and then travel down the Mekong through Vietnam, to Laos and Thailand by rail, river boat, bus and truck before setting forth on my much longer trans-Asian journey. From Bangkok, I went on to Rangoon, Akyab and Chittagong proceeding by rail-ferry up the Meghna through Dhaka and onwards by train to Calcutta and India.

In hindsight I am astonished at my audacity in assuming, despite many warnings, that I could travel overland by myself through South Asia to London. No one I knew seemed to know of anyone who had actually done this. Being young, I was confident that I could. I seem to have been fearless for I have no recollection of either apprehension or doubt.

Travel in 1950 was slower and more deliberate than it is now. Oceans were crossed in more leisurely fashion aboard ships. Air travel was for the affluent. Trains, buses, ferries and, in ‘developed' countries, hitch-hiking, were the modes used by students. Few stayed in proper hotels. Most sought inexpensive hostels. Where possible you looked for opportunities to stay with friends or friends of friends, drawing upon the social network built as you met fellow travellers, shared information and passed along the ‘wisdom of the road'.

Letters of introduction and calling cards endorsed, "To Introduce", were the international currency that opened doors to institutions and people who could be helpful. These attested that you were likely to be of good character, reasonably civilized and known to a mutual friend. The system had the great advantage of linking one to a network of local residents who could help you to see interesting places and meet interesting people. It also normally assured a simple, safe cuisine, a clean bed and toilet facilities at a modest cost. The disadvantage was that you could become entrapped in a comfortable cocoon that limited contact with the people and culture you wished to learn about.

Modern conveniences were rare. Air conditioners were still punkahs (fans, hand operated). Communication was tenuous. Satellites, cell phones, the internet, fax, e-mail and television were yet to come. Outside the cities, even telephones were scarce. Few locales beyond cities were electrified.

However, the Postal service, the telegraph and the railways were excellent, reliable and inexpensive. Mail could be counted upon and, when time was critical, short telegrams served to confirm arrangements and glue the social fabric together. One learned to anticipate, make contingency plans and to write well in advance.

Calcutta

Sealdah Station, Calcutta (now Kolkata), in the middle of the night of the 10th of July, 1950 was a shock. First impressions remain vivid. As the train ground to a stop, I realized that it would be difficult to get off, for the station platform was packed with sleeping passengers seeking passage to East Pakistan. The Dhaka bound ‘refugee' train departed only infrequently and was always over crowded. Therefore, thousands simply lived on the station platform until they could get on board. The scene was, to me, unbelievable. Sleeping men, women and children were wedged so closely together that one had to gingerly walk on tiptoe to avoid stepping on human bodies. This was my welcome to India.

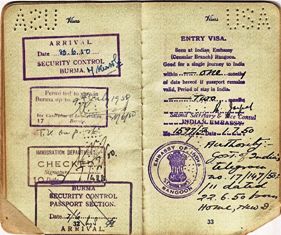

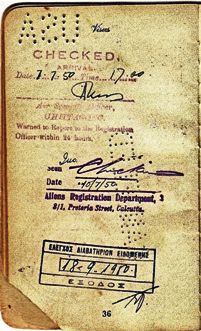

Once through the station gates, I was concerned that my passport had not been properly stamped for entry when, in the middle of the night, our train crossed the border. Amidst a chaotic customs inspection, I had found no official who appeared interested in formally admitting me into India, a lone foreigner among the multitude crowded in our carriage. I approached a sleepy border policeman, who reluctantly leafed through my proffered passport upside down and smilingly handed it back. I had to trust that I could sort out my status in Calcutta. I searched for the immigration office, found it closed and copied down the Pretoria Street address of the Alien Registration Department, where I reported later that day. All was then well.

My ‘means' were severely limited for I had left Samoa with just $500 from the sale of my jeep. A year later, I was dependent upon the savings accrued from my work in the goldfields and on the tin dredge. Despite this, I had learned that it was best to stay at a respectable hotel when making first contacts in a new place. I therefore registered at the upscale Grand Hotel for what remained of the night.

In India my letters and notes of introduction from friends to their friends along my planned route were to prove invaluable. I had such a note from a friend in Malaya to a Methodist missionary, Rev. Homer Morgan, living in Calcutta. I thought that I could not impose upon him in the pre-dawn of my arrival so it wasn't until mid-afternoon after I arose, registered as an alien and collected my mail at the American Consulate, that I presented myself at Rev. Morgan's. He was expecting me and immediately insisted that I move from the Grand, even though a visiting Bishop from ‘up-country' was already staying with him.

They were both pleased to see me, to hear news from colleagues in Malaya, and to graciously respond to my many questions. They had learned of my coming through a letter from a retired missionary lady, Miss Clancy, who had befriended me in Kuala Lumpur. They were also holding a detailed letter of instructions from Joe Gann, a Canadian ex-military type who, after the war, had decided to "stay on" to become a Buddhist Lama. A mutual friend had told him of my impending visit and of my interest in Buddhism. Though Joe lived in Lucknow he had written that he planned to meet me at Patna to escort me to Bodh Gaya and Sarnath if everything worked out. Thus was charted the initial phase of my transit of India.

During the following days I walked along Chowringhee, across the Maidan, to the Victoria Memorial, the Fort and other sights. I took only a few photographs, for colour film was both precious and often unobtainable. The massive bridge to Howrah, the burning ghats, the temples at Kalighat all were impressive and Calcutta itself something of a surprise.

I do not know what I had expected, but the city was much more metropolitan than I had anticipated. The devout worshipers immersing themselves in the Hooghly were exotic, but fascinating while the huddles of thin men in worn and dirty dhotis pushing huge, heavily loaded carts along Calcutta's rainy streets amidst trishaws and pedestrians while dodging cars, buses and trolleys were a shock. They, more than the endless streams of drably clad people in their greyish-white dhoti's and saris moving at a slow, destiny-driven, pace on endless errands, brought home the reality of population density and of poverty. Though the use of humans as draft animals seemed inherently wrong, I accepted it as normal and thought little of the great injustice involved.

Because I had lived for years with and among the island people of the South Pacific and had supervised a disparate multiracial crew aboard the tin dredge in Malaya, I was not generally affected by what later came to be called "culture shock". Nevertheless, India's sheer population, its scale and density, took some adjustment.

I was delighted to find that India's national newspapers were published in English and of a high editorial standard. Also pleasing was the slow realization that excellent English was spoken so widely among the educated and that pigeon "Hinglish" was, de facto, the secondary language among many of the less well educated.

The monsoon climate was oppressive for Calcutta's moist air enveloped me\; the humidity relieved only briefly following the mid-afternoon monsoonal downpour. Black umbrellas and Gandhian khadi were dominant under endlessly overcast skies. Bright saris were infrequently seen. I was not harassed by street beggars nor followed by hoards of children. Rather, I remember the civility encountered whenever it was obvious that I needed assistance. Though I knew nothing then of Bengali culture, I found Calcutta most civil.

Bodh Gaya

I set off for Patna by Indian Railways. Travelling third class was an experience not readily forgotten. With only smiles, sign language and limited phrase book communication on either side, I was able to lay claim to a place to sit from which I could see something of the countryside while maintaining congenial relationships with the many who shared our compartment. They were, fortunately, gentle folk, both accommodating and friendly, though understandably curious. It was for me an adventure, viewing the agricultural countryside dotted with self-contained villages and fields of farmers tilling their crops.

Arriving in Patna, I learned that my Guru, Joe Gann, had unexpectedly been called to Kalimpong. I was, of course, disappointed but after looking around Patna and discerning nothing visible of the historic Pataliputra of the past, I decided to proceed to Gaya.

In Gaya, I hired a bicycle rickshaw or trishaw to pull me to Bodh Gaya. I had no idea that it was seven miles away and as the miles rolled on and the sun grew ever more warm, I became uncomfortable and increasing guilty as I watched the driver's thin legs pumping strenuously up and down. I wanted to suggest that he ride while I pedalled for a time. All I could do was insist on rest stops. This encounter confronted me with a moral dilemma. I knew that in a better world we should not accept such injustice based on race, caste and economic status but I did not find the courage to challenge the system. I suppressed my guilt but carried it within me.

From Bodh Gaya onwards I had only Joe Gann's written guidelines. It took a while to locate the drab and untidy dharmasala. I was disappointed. Still, I was welcomed and quickly accommodated. The Bikku provided me a mat in an open courtyard, where I was to sleep among the monks, some of whom purported to remember the "Canadian" Lama. Between them, there was sufficient English to give me a sense of Bodh Gaya's historical significance but it quickly became apparent that I would be unlikely to deepen my understanding of the philosophical underpinnings of Buddhism while here.

The serenity of the unique Mahabodhi temple, set amongst trees, allowed me to imagine the struggles of Gautama as he approached his second birth beneath the "tree of enlightenment": the Pipal or Bo. I had first been attracted to Buddhism when reading that Gautama's followers taught that the salvation of mankind lay in self-renunciation and inward self-control. Unlike the West, where we sought to control nature, we should first seek to control our desires and to live in harmony with nature. During my travels in Thailand and Cambodia I had wanted to learn more. Though I had been raised in the bosom of the Episcopal Church, I found Buddhism rational and appealing. Under Joe Gann's guidance this influenced my Indian itinerary.

The Mahabodhi temple of Ashoka's time had been demolished and frequently restored, most recently during Lord Curzon's Viceregal administration though there seemed to be a long term controversy between Hindus and Buddhists about the site. I found the sacred Pipal tree, undoubtedly a descendant of the original, and it kindly gave up a leaf to me that I have preserved to this day. Revelation of a stone designated ‘the diamond throne', said to be the ‘centre of the universe', left me unsure how it related to the Buddha or his teachings save that he was seated upon it when he was enlightened. As twilight approached, I was summoned to meditation, after which we were served a meal of rice and vegetables on a leaf tray. Then, after bathing, I retired.

The night was not restful for I was beset by small biting creatures which, even if I could have seen them, I would have been hesitant to squash. In the morning, feeling a bit queasy, I declined the morning meal and, after meditation made my farewells. I then sought assistance in obtaining a horse-drawn tonga to take me to Gaya where I boarded the first train to Benares.

Benares

In Benares (now Varanasi), I had a note of introduction to the Theosophical Society. I knew nothing of the Society, its objectives or its history. Nor did I realize how closely interwoven as it had been with the Indian National Congress. I was soon to learn for I was warmly welcomed by a gracious gentle lady of mature years who immediately invited me to join her for tea. She might well have been an incarnation of Madame Helena Blatovsky, the Society's founder, or of Mrs. Annie Besant, a later President of the Society who had also been President of the Indian National Congress for many years. Even now I am uncertain whether she was English or Indian, she was so poised and sophisticated that I was charmed. In response to my inquiries she thoughtfully expounded the tenets of theosophy with its goal of a universal brotherhood of all humanity and peace without distinctions of race, colour, caste or creed. She was quite captivating and, for me, this was an enthralling experience,

Following tea, I raised the issue of accommodation. She unhesitatingly invited me to stay and showed me to a guest room. I insisted on paying the modest charge, after which I was advised to walk to the Ganga, being instructed to return for dinner, given a sketch map and sent on my way.

Benares seemed dynamic. People moved at a more rapid pace. The myriad temples, the ghats and the throngs of bathing pilgrims presented scenes both chaotic and hypnotic. My puritan ancestors would surely have been shocked beyond belief as I examined the explicitly erotic pillars supporting the tiered pagodas of the Nepalese Temple, opening whole new vistas of Tantric art that I had yet to explore. Before sunset I returned to dinner and further conversation with my hostess. I slept very peacefully that night.

Rested, the next day I visited Sarnath where Gautama Buddha had delivered his first sermon. The Ashoka pillar, which was to become India's national symbol, was found there. The atmosphere was serene, the museum filled with treasures. The sculptured stone was both extensive and exquisite. I soon realized that to reflectively appreciate Buddha's "Deer Park" demanded more time than I then could give. Sadly, I never again visited Sarnath. Returning to Benares, I caught the brilliant sunshine magically lifting the temples so that they appeared to float, luminous and dreamlike, atop a gauze of smoke from the burning ghats along the holy Ganga. An indelible memory.

That evening I learned that Prime Minister Nehru was to visit the following day to give the convocation address at Benares Hindu University. I very much wished to see and hear him, so stayed on. Crowds were enormous and once I started to follow I was swept along in the procession. Jawaharlal Nehru was then regarded as nearly divine, perhaps symbolically replacing the tragically deceased Gandhi in a contemporary pantheon. I thought myself especially fortunate to be able to actually see him. Though he spoke in English I could hardly hear him for the loudspeakers repeatedly broke down. Later obtaining a copy of his address, I saved it for many years. Nehru seemed the embodiment of all India's hopes.

Allahabad

On Wednesday, July 19th, while riding aboard the train to Allahabad I became ill. Fortunately I had a letter of introduction to Dr. H.N. Stuart, the Principal at Holland Hall, Allahabad University. By the time I reached Allahabad Station I was navigating with some difficulty. An unknown Indian gentleman, sensing my distress, asked if I was a student then helped me obtain a rickshaw that delivered me to the front gate of Dr. Stuart's residence. There, I was just able to walk up the stairs and present my ‘chit' (introduction) to the bearer before collapsing. The bearer, seeing I was ‘unwell', invited me in from the verandah and suggested that I sit on the sofa to wait. By the time he returned with hot tea and biscuits, I was sound asleep and remained so until the kindly gentleman scholar who was to be my host for the next few days returned from his classes and awakened me several hours later.

He took my temperature and summoned an American lady doctor, Dr. (Mrs.) Barar, who determined that I was suffering from a non-lethal fever, general exhaustion and food poisoning. In 1950, broad spectrum antibiotics were not routinely prescribed, so I was given APCs, aspirin tablets with codeine known in the Navy as an "all purpose capsule", and paregoric, a tincture of opium compound to calm the stomach. She told me to slow down and take ‘bed rest'.

That night and the next day I did just that in Dr. and Mrs. Stuart's guest room while browsing in their extensive Indian library. Later, I was shown Allahabad's sights and the University by various faculty members, who requested me to give informal lectures on Samoa, the South Pacific and my recent travels. I was delighted to do so.

Lucknow

When, after a few days, it was time to move on, Dr. Barar advised me to travel to Ranikhet in the Himalayas to recover my strength in a cooler ‘Hill Station' clime. She gave me an introduction to a friend there who was sure to look after me.

Meanwhile, I had promised both Bishop "Rocky" in Calcutta and Joe Gann that I would visit Lucknow, where Joe insisted that I must use his rooms for as long as I wished. I had also met Bob Steele, a student from Ohio State, working for the American Friends Service Committee in Lucknow. He promised to show me around.

After settling in, we borrowed bicycles and did the sights after which Bob introduced me to friends and faculty at Lucknow University. They too requested that I give some informal talks. We had dinner at Isabella Thoburn College, a ladies institution that was blessed with many attractive and flirtatious young students. I enjoyed lecturing there.

The legacy of the "Great Mutiny" of 1857 remained a centrepiece of expatriate lore in Lucknow. The history of Oudh itself seemed to be less well known. I made the mandatory pilgrimage to the Residency and remember the subterranean rooms that, although built to provide a cool respite from summer heat, had afforded protection from shelling during the siege. Despite their protection, the gallant Sir Henry Lawrence was killed by shellfire on July 4th, 1857.

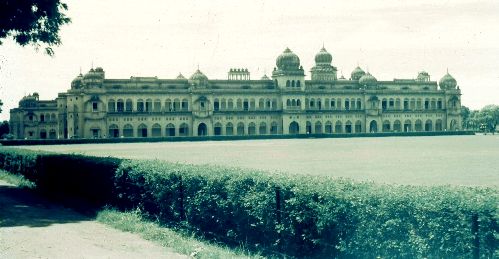

More impressive than the Residency ruins were the Great and Chota Imam Baras and the other large, numerous and rundown palaces and edifices built by the rulers of Oudh. I could learn little about them, except that the British Governor General, amid considerable controversy, had broken a treaty with Oudh, then proceeded to dispossess the Nawab only a few years before the Mutiny\; the "First War of Independence". That war was, of course, attributed to "pork fat", not related to the treaty violation or usurpation of sovereignty.

Ranikhet

Leaving Lucknow, I took the narrow gauge train to Ranikhet, where I saw the spectacle of Nanda Devi, some 25,645 feet high, looming snow capped on the northern horizon a great distance away. That first view of the Himalayas may have foreshadowed the many years I was to later spend in Nepal. Though Dr. Barar's contact was not "on station", I found a guest house for the night.

There was something sad and rather derelict about Ranikhet that mid-summer. It should have been crowded with holiday makers. Instead, it appeared empty and slowly decaying. I was happy to depart to return to the plains and make connections for Delhi.

Delhi

India's capital was a dramatic contrast. Old Delhi was alive and faster-paced while New Delhi still had the feeling of a city "in progress". Its great imperial edifices: India Gate, Rashtrapati Bhawan, and the Parliament, had been built as testimony to the permanence of the British Raj. Now that Raj was gone and the Government of India was in its early days, slowly feeling its way. In the heat of that summer of 1950 it seemed a vacant stage, waiting for the play to begin.

After some searching, I located the splendid new, yet incomplete, American Embassy and was delighted by its neo-classical lines that, with its many idiosyncrasies, still endure. There, I collected my mail and called upon the Naval Attaché, Captain Courtner, to help me to clarify my status as a reserve officer, given that the US was fighting in Korea. He invited me to his home where we talked of mutual friends in Samoa and my years in the South Pacific. My recall to active duty never came except for short periods in Germany and with the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean.

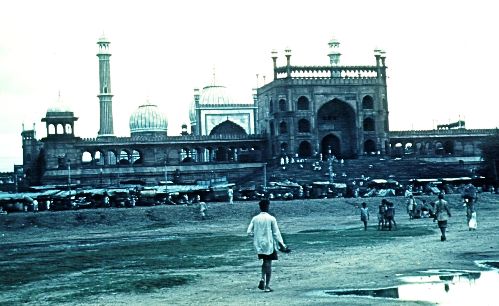

Though he invited me to stay, I had already confirmed arrangements at a missionary guest house on the ‘Ridge' in Old Delhi. That was quite a different ambience. As it was situated near the Mutiny Monument, I was again regaled with stories of 1857 and British ‘derring-do' against the mutinous sepoys while storming Kabul Gate. The shameful post mutiny demise of the Mughal Empire was not mentioned. The Red Fort, the Diwan-i-Khas, the Purana Qila and the Jama Masjid attested to the grandeur of earlier empires while the symmetry and elegant grace of Safdarjang's Tomb spoke to the architectural genius of the Mughals and their Persian architects. In two hot days I realized that Delhi was far too large for walking and that I was not indestructible. I did manage a visit to India's Parliament in session as foreign students, it seems, were welcomed. Today, I fail to recall the issues then being discussed but I do know I was impressed by the formality of the proceedings.

Taj Mahal and Fatehpur Sikri

Next I was off for Agra and the Taj Mahal. I stayed with John Pollock, a Western Pennsylvanian like myself, then teaching in a mission school. He was pleased to have company and was a source of useful ‘inside' information about the educational system. He took pains to show me the Taj, the Fort and the lovely Itimad-ud-Daula across the Jumna. The following day I found my own way by bus and rickshaw to Akbar's tomb in Sikandra and to Fatehpur Sikri, a self-contained city of delight about which I had known nothing.

In the first days of August, 1950, Fatehpur Sikri was deserted\; certainly no tourists and few others were ‘out in the mid-day sun'. I had Akbar's greatest city, a vast complex of superb red sandstone buildings, to myself. I strolled unguided and unhindered for several hours as my mind conjured visions of the lives of those many princes, viziers, servants and slaves, who had walked these splendid courtyards, played royal games, bathed in these pools, made love and, in the end, were caught up in intrigues, conspiracies, jealousies and bloody plots only to be driven from this glorious city by omens and for want of water. It was difficult for me to leave\; how much more so for them.

Ajanta, Ellora, and the Gurkhas

The pressure of time was at my back for I knew I must get to London by September's end for the university's fall term. So, despite my desire to explore Agra further, I departed for Aurangabad.

The third-class train compartment I crowded into was designated for twelve passengers but I counted forty-two, not including those hanging on the outside. By skilful manoeuvring, I managed to claim a niche on a wooden bench, where I wrapped myself around the small Marine Corps pack that contained my belongings.

As evening approached, my fellow travellers produced hot, sweet milky tea, which they generously shared. Thank goodness I was able to dispense a packet of sweet biscuits in return. We rolled on through the night. Occasional station stops afforded the only chance for snacks, drinks and toilet facilities, at which time one had to trust fellow passengers to guard your seat and possessions. My surrogate ‘family' looked after my interests.

Not until the following afternoon did we arrive. It was an exhausting journey and I was glad that I had sent a confirming telegram ahead, advising a friend of my mentor, Joe Gann, of my arrival. His friend was a Major Freemantle of the formerly Royal Gurkha Rifles, now part of the Indian Army. I was apprehensive that he might prove to be ‘a bit stiff', as I had found some English officers in Malaya. I was delighted to find him relaxed, hospitable and waiting for me at the railway station.

We jeeped off to his Mess for a wash-up, tiffin, and then to his quarters for a siesta before evening drinks. Later, the ‘Saturday Night Frolics' in the Gurkha Mess gave me insight into a previously unknown military tradition. There was a mixed bag of Gurkha officers: some English, some Indian. This was a critical period of adjustment for the Gurkhas as the eleven regiments had been, post-Independence, divided between the British and the Indian Armies. Their parting after more than a century had been heart-rending for many. The courage of the Gurkhas in battle was well known. The abiding affection that both the Indian King's Commissioned Officers and their now departing British counterparts had for ‘the Brigade' was deeply moving. For many of the British, the Gurkhas had been their life. Dinner amidst the splendour of that Gurkha Mess conjured visions of past glories that remain vivid.

Bed tea arrived early. I roused myself, and was soon on board a decrepit country bus headed for the Ajanta caves. Sixty miles over an unimproved road shook me awake and brought me to the foot of the unique caves, with their ancient sculptures and frescoes that make this a cultural treasure for all mankind. The wall frescoes depict sagas of Buddhist mythology and Indian life from very early times. As I climbed to reach their entrances I found it was again extremely hot. This was not the ideal season to visit Ajanta.

Though the cave's interiors had little lighting, the impact of the ornately carved stone entrances, pillars, wall paintings and statuary was staggering. The scale of the earth-moving and stone-chiselling endeavour required was simply enormous\; comparable in its time to the Panama Canal but without mechanical help. It was a world monument both to religious devotion and to the hand labour of thousands of devotees and/or slaves.

By early afternoon I was becoming dehydrated and retreated seek ‘iced' drinks of dubious origin at the bus depot kiosk. The last bus took me back to the ‘safe haven' of the Gurkha Mess for dinner and for a last evening of good company with the Gurkhas before bed.

On Monday, I travelled to Ellora where, per Joe Gann, I devoted the day to the study of Indian art from the early Buddhist and Jain periods to the voluptuous loves of the later Brahmins. Here again the sheer scale of the enormous stone temples and sculptures, their detail and the artistry, were breath-taking, Unfortunately, after Ajanta, I had almost reached a saturation point and took only a few photographs before returning to Aurangabad to rest before going on to Bombay.

That evening, bidding farewell to the Gurkhas and to my host, Major Freemantle, I boarded the overnight train.

Bombay

When I reached their hostel in Bombay (now Mumbai), I found Bob Steele and his friend, Glen Fuller, were expecting me. As we sorted out plans, I learned that Bob had changed his mind and had decided to fly rather than accompany me onwards. I had neither the money nor the desire to go by air for I was determined to proceed overland. Therefore, I made Bombay's Consular circuit to seek required visas. This was easier than I had expected for I was quickly granted the critical ones, and by Thursday afternoon had assurances that the others would be approved and might be collected at the appropriate Embassies in Karachi or Teheran.

This left some time for sightseeing next day so we took the launch to the Elephanta Island to view very early cave sculptures, returning to have lunch near the Gateway to India and proceeding later to have a fancy high tea with an obviously affluent Indian friend of Bob's on Malabar Hill. Though disappointed that I would not have a companion during my onward trip, we parted as friends with plans to meet again in the US. We never did.

To Pakistan by train

Late Friday, I left Bombay and travelled north through Baroda and Ahmadabad to Marwar Junction. There, I transferred to the Jodhpur State Railway that carried me to Barmer and Munabao, the last station before the Pakistani frontier. The train was filled with Muslim families relocating to Pakistan for, although the border was ostensibly ‘sealed', refugees were arriving every day and, apparently by mutual agreement, were permitted to cross into Pakistan.

In the pre-dawn light, the train stopped. I could see no settlement. This was the end of the line and there was only a small railway station. During immigration and customs inspection, my passport was scrupulously examined for I was the sole Westerner. The numerous visas and stamps from earlier travels seemed to arouse curiosity and, clearly, I was something of an anomaly since few foreigners passed this way.

My fellow passengers had assured me that a Pakistani train would be waiting just over the border but that we would have to walk the next mile to the frontier. We were to wait for clearance before departing. While waiting, I wandered the desolate countryside near the railway station taking an occasional photograph. I later learned this was a violation of security rules. Unfortunately, I compounded the breach by climbing the ladder of the small water tower to get a view of the railway station, an error I was soon to regret.

Editor’s note: Train service between Munabao and Pakistan was suspended in 1965, and reopened 41 years later in 2006 (left), when the Thar Express (below) came to Munabao from Pakistan.

A guard signalled that I must get down and accompany him to his Subedar, the Officer-in-Charge at the Check Post.

I realized that a low-key apology and denial of any subversive intent was my only conciliatory course. This did not prove sufficient. The Subedar now thought that he should probe more deeply to determine who I really was. Why was I travelling through this remote border area? I explained that I was a student travelling overland to England. He found this unusual and observed, correctly, that my passport stated that I was a teacher. I explained. He had doubts and remained unsure what he should do. He departed, taking my passport with him. While I waited, the other passengers were given permission to leave.

I affected to be unconcerned. However, having no passport, I was fearful that if he failed to return in time, I would not make the connection. After what seemed like an hour, the Subedar returned but revealed nothing. Frustrated, I quietly but ostentatiously obtained a telegram form from the Station Master and, in bold block letters, drafted a message addressed to "The American Ambassador," "Attention Captain G. Courtner, U.S. Naval Attaché", "American Embassy, New Delhi" printing my name and rank below. This shadow play, surreptitiously observed by all, had the desired effect. Before I could move to send my innocuous ‘thank you' message to Captain Courtner, a cup of tea arrived, my passport was handed back and, without further admonition or censure, I was advised that I might leave. As I started down the railway track, the Subedar saluted and gave me a handshake.

Before I reached the Pakistani frontier, I could see the Hyderabad train chugging away. I was warmly welcomed by the young Pakistani Officer-in-Charge at the frontier check post. He had been regaled by my earlier travelling companions with a greatly exaggerated story of "the American" who had been held as a "Pakistani spy" by the Indian Army. This seemed to be, for them, the source of much amusement. Having missed the train, they accommodated me in the officer's tent, fed me well and treated me to a full "Independence Day" review by the Sind Border Guards the next morning before I went off to Hyderabad and onwards to Karachi.

My trans-Asia odyssey continued and good fortune travelled with me all through the uncertain Middle East, across Europe and to England, where I landed safely by ferry at Folkstone on September 30th.

Epilogue

My brief transit through India was a peak lifetime experience. I reflect now in amazement that it was possible to see, do and learn so much. So many doors were opened and so many good people shared their thoughts, homes and hearts. I was, it seems, blessed.

As a Jesuit scholar of India had observed some centuries earlier, “The onion that is Hind grows ever larger as one peels away each layer.” I had barely scratched the first outer peel but had learned a great deal about how little I understood.

I departed with warm memories and glorious images that are still vivid. That journey was to influence my career and enrich the remainder of my life.

© John Cool 2009

Comments

Add new comment