Latest Contributions

Dadu, our grandfather (1869 – 1953)

Category:

Tags:

Suchandra Banerjee (left) was born in 1939 to Tapogopal and Usha Mukherjee. After she got married to an Army officer in 1958, she made her husband's family and the Indian Armed Forces' family her own. She moved with her husband from city to city, ending in Lutyen's Delhi when her husband, late Lt. General Ashish Banerjee PVSM, served as the Director-General of the National Cadet Corps. Known as a person of great spirit and generosity, she has helped several people, outside her family, whose start in life was disadvantaged. She nurtures a large extended family and contributes to endeavours and institutions serving to uplift communities and the arts. She lives in Noida in the home she retired to with her late husband.

Shreela Bhattacharya (right), born 1934 is the senior most scion of the present generation of the Mukherjee family. Upon her graduation, she married Dr Saurendra Kumar Bhattacharya, a brilliant bio-chemist. They lived in the UK over 1956-1959. They settled in Mumbai in 1965. Soon after his retirement in 1988, Saurendra passed away. Shreela continued to live in Mumbai, devoted to her family and close friends, Tagore's music and literature. In 2010, hampered by visual impairment she moved to her son's home in the Netherlands, where she lives a quiet life. She returns regularly to her home in Mumbai and ancestral home in Kolkata.

Editor's note: Suchandra Banerjee is the principal author. Her daughter, Leena Brown, submitted this story.

In 1926, my Dadu (paternal grandfather), Rai Bahadur Pran Gopal Mukherjee, was the Deputy Post Master General in Dacca. This was a prestigious and well-paying job that only a few Indians were privileged to hold at that time.

Dadu's Rai Bahadur Turban

Dadu's Rai Bahadur Medal

Dadu had been a man of the world. He loved non-vegetarian food and parties\; he was a crack shot. One night, after partying, in a dream, he saw his father reprimanding him and saying he was shocked with his indulgent ways. On waking up, he reflected and without telling anyone went to Varanasi, where he did prayaschitta (atonement), and renounced his worldly ways. This is how his journey began towards becoming an ascetic.

He took premature retirement from his job, and moved with his wife Surobala and youngest son Gobindo to his Guru Sri Balananada Brahmachari's ashram.

The ashram was located in Karanibad in Baidyanath Dham, an abode of Lord Shiva in Deoghar, Bihar. He gave up all his worldly belongings, placed them at his guru's feet, and embraced vairagya (renunciation). He lived like an ascetic and was known as the shukla sanyasi (hermit clad in white, to denote purity in his case). My grandmother lived just outside the ashram complex in a house called Ganga Ashram.

Dadu stood tall. He was stately, erudite with a flowing beard and a tuft of grey hair on his bald pate. His attire was simple, a white dhoti and angavastra (unstitched cloth to cover the upper torso) with a pair of wooden khadaon (footwear) that adorned his feet. People looked up at him in awe and reverence. Yet, he was so approachable. When he came to Ganga Ashram for his meals, I would hold his finger to take him to the mogra (white fragrant flower) field and point out the many hued butterflies or reflections on the wings of dragonflies or some insect\; he would always participate willingly.

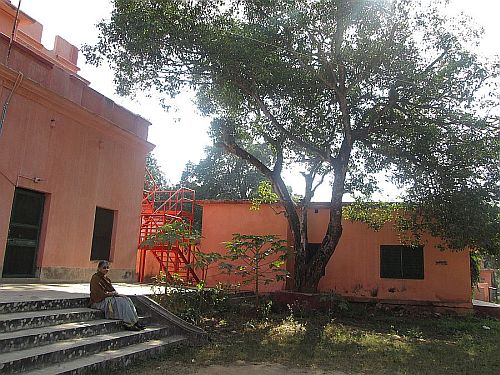

His home was called Santosh Ashram. It was a small yellow square building with a reddish gravel dirt road around it, and a raised platform on three sides of the house. On the left of the house was a beautiful bakul (star-shaped fragrant flower) tree with star-shaped fragrant flowers and bright orange fruits, which left an astringent after taste. Half the house was a library.

Santosh Ashram, Deoghar, Bihar

The other half was basically two rooms, where he lived. There was an enclosed courtyard with a rest room in the corner, steps going up to the high walled terrace, and a few more steps to the barsati (roof top room), which he used for meditation. It had a wonderful fragrance of agrabatti, old books and flowers. There was no electricity, running water or telephones. No noise pollution of moving vehicles, only the occasional sound of a car or a tonga. There were beautiful gardens surrounding the home, large open spaces beyond and a sense of all-encompassing love.

With Dadu lived a big tomcat, grey with black stripes. His mother had abandoned him under a staircase. Dadu had found him and hand reared him. We called him dadur beral (dadu's cat). Although completely devoted to Dadu, he was not friendly at all. If we tried to pet him, out came the claws, and he would try to wrap us. Since Dadu's house had only drinking water - no food - he would come with Dadu to Ganga Ashram for his meals. He would always walk ahead of Dadu, his tail sticking out like an aerial, the tip slightly bent. Many a time he saved Dadu from stepping on snakes at night. .

Dadu used to let him out first thing in the morning when he went upstairs to meditate in his meditation room. He often wondered how he always found the cat waiting for him outside his barsati door as if listening to his chants. So, one day he let him out, went upstairs and watched. The cat eased itself, climbed on to the bakul tree, jumped onto the terrace wall and climbed down to get to the barsati door. After my Dadu passed away, he was missing. He was found dead after a few days, lying in front of the entrance door. I often wonder who he really was.

As children, during summer vacations, we visited our grandparents at the ashram. We took the overnight train from Patna to Jasidih, where an ashram staffer would always receive us. Either it was the driver Badrimama with his station wagon, or someone else who would huddle us into an awaiting tonga. We were allowed to roam free in the ashram complex except for the water bodies, which were taboo. We would find Dadu sitting behind his round Italian marble table with ornate mahogany legs with the cat purring at his feet. On his table were books and papers with paperweights made by us. Chota, our youngest uncle, had taught us to collect the lead foil in which tea leaves came packaged. We would melt these, pour them into clay or wooden sandesh moulds, and let them solidify into objects that we used as paperweights.

In the evening, a kush (grass asana or mat) was spread, and a woollen asana (mat) was placed on top of it for Dadu. This is where he sat in padmasana in the verandah with visitors sitting on mats. People came from all walks of life to hear his discourses and to engage him in discussion. Among them were eminent people from Varanasi and Kolkata, such as Sri Krishna Prem (Ronald Henry Nixon), Moti mai Madhavashis who came all the way from Mirtola in Uttar Pradesh, Dilip Roy, Anandamoyee Ma and so many others. As dusk fell and the glow-worms came up twinkling, Hingna or Jharia Mahato, the tribal boys who did the heavy work of cleaning, drawing water from the well, and taking care of the cows, would bring out the kerosene lamps their glass shades polished with dry charcoal ash.

I loved spending my morning hours with Dadu. He would suggest what I could read. I would discuss my readings with him or read aloud to him when he sat down for lunch.

As I entered my teens, Dadu's health started failing. By this time, his house had been electrified. Doctors came from Kolkata to operate on him. But it was to no avail. He was suffering from cancer which had spread. The last time I saw him was in 1953 when I had to go back to school to Nagpur. He was sitting on his bed, gaunt, pale and listless, a shadow of himself. I knelt down to touch his feet, and he placed his hands on my head. No word was exchanged. A few weeks later news came of his passing away. This was my first experience of death of a dear one. Back then, I did not realize the august presence we grew up in.

_______________________________________

© Suchandra Banerjee 2016

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people\; the comments must related to the story. The purpose of the approval process is to prevent unwanted comments, inserted by software robots, which have nothing to do with the story.

Comments

Add new comment