Escape from East Germany 1972 by Kailash Mathur

Category:

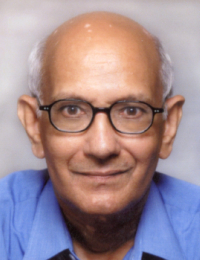

Kailash, called Chanda by his parents, is an electrical engineer, who was born in Tijara, which is even now a very small city in Rajasthan. He lived in East Germany from 1965 to 1971, where he married Annemarie, a German, in 1969. Since 1971, he has lived in Vienna, Austria. He became a widower when Annemarie died of cancer in 2004.

Getting in

Taking off from New Delhi’s Palam airport, the Aeroflot plane flew over the Himalayas and over the vast planes, lakes and mountains of Russia, which was a part of the Soviet Union at that time, and finally landed in Moscow. It was the middle of winter, 30 December 1964. What a shock for the 24 year-old Indian man from the desert state of Rajasthan who had never flown before in his life and had never even dreamt of seeing the snow covered Himalayas and other vast tracts of this planet! The young man was delighted.

Next day another plane took me to East Berlin, the capital of East Germany. It was snowing on that last day of the year, a special day in Europe, celebrated with lot of drinks and fireworks. Was it cold? It did not make me shiver, rather I was amazed, my mouth left wide open. Where was I, and how on earth was I going to cope with life here?

A German received me at the airport, and got me seated in a train to Leipzig, my destination. He told me that I had to go unaccompanied. He gave me some money and an address for a taxi driver. I asked him, “How will I know that I have reached Leipzig?” His answer was, “The passengers will tell you.” Since I had learnt some German while studying electrical engineering at Roorkee University in India, I was not really shocked.

I can still see myself sitting in that double-decker train to Leipzig and still remember the jolly taxi driver, who dropped me at the hostel gate of Herder Institute on Lumumba Strasse. (I had come here to learn German before going on to Dresden for my Ph.D.) I had to press a button until somebody opened the big gate and handed me the key of my room in the nearby building. It was already dark in the evening, and it was very chilly.

I lugged my luggage up the stairs, found my room, inserted the key and turned it around, as we would do in India. But the door did not open. I turned it both ways and still it did not open. I had no choice but to go back to the reception. And I came to know that in Germany you have to turn the key twice to unlock the door.

The room was big and had many two-tier beds, but it was empty. I was thoroughly tired after the long journey and decided simply to go to sleep without eating. I woke up in the middle of the night, hearing strange loud voices. As I felt afraid and could not make out what was going on, I did not move and pretended to sleep.

Next morning I found out that the voices were of young men from Ecuador, who had been out celebrating the New Year until late in the night, and had come back drunk. They were very friendly to me, and we became good friends. Soon I met other Indian students who had also arrived recently. With them it felt like at home because they cooked Indian food and played Indian music, while I still had to learn cooking. On the other hand, I was used to eating meat, was more Europe oriented than they were and spoke slightly better German than them. So, I could help them out in adjusting to Germany.

After the New Year holiday, we began our intensive course in German at the Herder Institute. This institute was famous not only for its excellent German teaching methods, but also for its political (communist) aims and teachings. We were some ten Indians in the class, besides a few Egyptians. All of the Indians were top-ranking students from various engineering universities, mainly from Bombay, Madras and Delhi. I was the only person from Jaipur, Rajasthan.

Our teacher, Mr. Günther, was a very friendly and affectionate person. Learning German was great fun, as I could mostly guess the English equivalent, though the pronunciation of German letters was quite different from that of the corresponding English letters. For example, the letter ‘a’ is pronounced as ‘aa’ in German. To help myself, I always thought of how the German words would be written in Hindi, which made it easier for me to remember the pronunciation. Much later, I learnt that both German and Hindi belonged to the Indo-European language group, and had lots in common, but I benefited from this link right from the beginning.

Together, we Indian students decided to speak German, and not English or Hindi, in our free time. Our progress astounded our teacher Mr. Günther! By June 1965, our knowledge of German language was deemed high enough for us to study for our Ph.D. degrees in German. As good as I was in learning German, my friend Shrikant was better. He was a Brahmin and well versed in Sanskrit. He led me in absorbing the surrounding German culture and we became friends.

Annemarie enters my life

One day two young girls, Annemarie and her friend Gerlinde, came to our classroom. They were on the verge of finishing their university course called “German for Adults”, and came to our class to practice teaching. Mostly they observed Mr. Günther, and it was only once in a while that they explained some aspect of the German language to us.

In one of the breaks, Annemarie showed us some of her books on India. She had been interested in India on her own for many years, had many pen-friends in India, and had purchased many books on India. She had read more about India than I had at that time. The Indian engineering students of those days were not reading books beyond their syllabus. Most of the Indian students thought that because they had lived in India, it was not necessary for them to read books on India.

It was only due to the general atmosphere at my parent’s home that I was interested in books. And, so it happened that I was the only Indian in her class (Shrikant was in a different class) who was interested in looking at and reading her books, and talking to her about her knowledge of India. Deep inside, I was ashamed that I had to learn about India in Germany by reading the books of a German girl. But I did not want this lack of knowledge to continue.

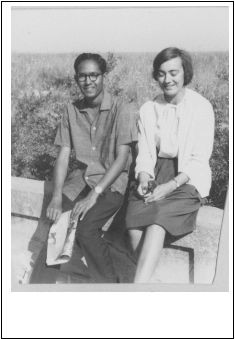

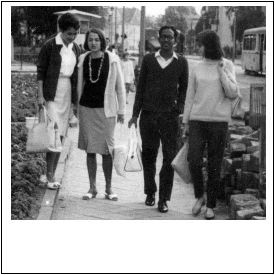

So it happened that I met Annemarie, and her classmates, Gerlinde, Anita and Karin, at many occasions. We enjoyed going for walks, shopping, theatre, cinema, etc., but were only good friends with no personal inclinations or attachments. I had taken the plunge into the German culture but not in to German life.

When a young Indian man goes abroad, the women he meets often have sexual norms quite different from those of Indian women. Mahatma Gandhi writes in his autobiography about how hard it was for him to fight his temptations during his first stay in England, and it was his strong religious background that helped him. Many of the Indian students in East Germany could not resist these temptations. Some had fathered children, and had either married hurriedly thereafter, or suddenly departed to India to avoid getting married. Some others avoided all contacts with German girls\; one of them would cross to the other side of road, if he saw any girl he knew coming his way.

Well, I had no such problems. It was easy for me to participate in the normal German life, which includes eating meat and heavy drinking, young people going on holidays to far away places on their own, etc. and yet to remain just friendly and morally clean. A good person keeping his distance, preparing for a future in India.

Long after Anne and I were married, Anne once asked me how I had resisted all her charms, during our holidays in Prague, Warsaw and other places. Well, my answer used to be that perhaps there is something wrong with me! What guided me more was my ignorance about the world of grownups and also a will to succeed in life, come what may.

Anne liked me very much. Later, when I was in Dresden (July 1965 – November 1969), she wrote letters to me every day. On some days, I got two letters from her! Her interest in India and me was astounding. Actually, it was beyond my imagination. Those were our happiest days. We ignored our cultural differences, though later we did face some difficulties because of these differences.

Understanding Europe

When I left India, I did not have a clear idea about life outside India. In particular, I did not know what life in a communist country such as East Germany was like, why Germany was split into two countries, what World War II had done to Europe, what Nazism was, and other aspects of European life and history.

No doubt, East Germany had many shortcomings, such as lack of things that were readily available in West Germany, and lack of freedom of speech. Yet, I had a wonderful time there. I had money, was free to take my own decisions, and the German people were very friendly. Roorkee University had opened my eyes to the world of learning, but here I got the opportunity to become a scientist, if I could.

The end of the intensive German course meant the start of holiday trips. Such holiday trips were unknown in India those days\; students in Roorkee University went only to their parent’s home in vacations. But in East Germany, there was no parental home, and you had to go somewhere in your holidays. Everyone was going somewhere, and you could hardly stay in the hostel during vacations.

I was on a scholarship of 470 East German Marks per month. The hostel room was free and food in the student canteen very cheap. This left me with about 400 Marks per month for other expenses. As we mostly ate our self-cooked Indian food, we spent hardly any money on restaurants. In later years, I started buying books, which were good and cheap in East Germany.

So, all of the students had money for holidays. All Indian students were going to Western countries outside the Soviet bloc but I was afraid to travel to the West. On my parents’ recommendation, I decided to travel to Vienna, Austria, a German speaking country with a great imperial past. I went by train to visit my cousin, Mr. Amba Prasad, who was working in the Indian embassy. He lived there with his wife and three children. They took me for a picnic in Viennese woods, which are beautiful. I was very impressed by the city, specially the trams, which ran frequently and punctually.

Just after I had returned from Vienna, Anne told me that she was going with her girl friends on a work-cum-holiday arrangement to Rostock, a seaside resort in northern East Germany, and invited me to join them. We had to earn our holiday by working at a building site. It was a typical arrangement for a socialistic country. The average citizen could not find a holiday place as the few nice places were all given to worthy workers or party members. At that time, East Germany was a state for Arbeiter und Bauern (workers and farmers), with foreign students and their teachers given the privileges of ‘workers’ in their first year.

We had to work for half a day each day. I dug some trenches, and had the rest of the day free for the beach side. We stayed in a students’ hostel with two persons in a room. One of my India classmates had also opted for this trip, but the idea of this type of holiday was alien to most of my other Indian friends. In those days Indians were not used to going for beach holidays, and would flatly refuse to dig trenches or do any other manual labour.

For the first time in my life, I had put on beach clothes, purchased in Rostock, and was lying in the sand, basking myself in the sun with four young women around me. I soon realised that I did not like beach holidays – but I enjoyed myself thoroughly. The women all found me friendly, pleasant and completely free from aggression or demand. We went for walks, to restaurants, to other nearby cities and talked and talked. Unlike India, cameras were affordable in East Germany at that time and I started learning photography. We just had fun like children!

A Mayday protest in Dresden

In July 1965, along with several other India students, I shifted to the Technical University (TU) of Dresden to begin my Ph.D. studies, while Anne remained in Leipzig. We lived in nice new hostel, close to downtown and the main railway station. Unlike Leipzig, which was an industrial city, Dresden was the historical cultural centre of East Germany, with a beautiful countryside. The Elbe River flows through the middle of the city, and there are a number of lakes and gardens, besides the surrounding woods and hilly area.

All the TU professors, teachers and the staff welcomed us Indians. After World War II, and the division of Germany, Dresden and the university staff were cut-off from the Western world. The professors, who had studied in the old united Germany, no longer had any contacts with West Germany, and were struggling for any contact with the outside world. So, foreign students, especially from a non-communist country, were welcome.

The professors invited us to their homes and treated us with respect, which was a huge change from my experience at Roorkee University. It was soon clear that these professors were highly educated elderly persons, recognized specialists in their fields who had published many articles and books in the old Germany.

At the same time, we felt the heavy hand of communist propaganda, which affected the East Germans more than foreigners. The main newspaper Neues Deutschland was simply unbelievable and unreadable – page after page, every day it reported the resolutions of the central committee of the SED, East Germany’s communist party. No one dared to criticize the government openly\; there was no free press and no regard for human rights.

May 1 used to be a very important day in East Germany. Mayday parades, to which all big institutions and companies had to send a delegation, were held in all big cities with lots of big political banners all around and ended with speeches by politicians. The main theme was that East Germans had a very nice life, while West Germans were being suppressed and exploited, and deserved to be liberated. Further, socialism was winning and spreading all over the world. Vietnam, where a war was ongoing against the West, was always mentioned to show how bad capitalism was.

On 1st May 1966 the Association of Indian Students in Dresden, of which all Indian students were members, also had to take part in the Mayday parade. We, the Indians from TU Dresden, decided to do something very naïve. As we went past our hostel, we shouted, not too loudly, in Hindi “down with Walter Ulbricht”\; Walter Ulbricht was East Germany’s chancellor (first secretary). Luckily, it went unheard! At that time, there were many Indians in East Germany, including Dresden, who had come on the recommendation of Communist Party of India, and admired East Germany politically.

The episode went unnoticed but even today it makes me shiver – how could we have been so reckless? After all, East Germany was a police state, full of spies, and you could never be sure whether someone was a spy or not. East Germans were still trying to cross over to West, many were shot dead at the boundary and many ended in jails. Almost anyone could tell you a story of some persons, who could escape to the West somehow and there were still people around secretly preparing to leave the country.

Social life in Eastern Europe

Anne invited her girlfriends and me for Christmas to her parent’s home in Goerlitz, a small city in the southeastern Germany, every year in 1966-68. So I got to know my future in-laws very smoothly. The Christmas and New Year parties were lavish, with lots of German food and drinks. It was like a constant mad celebration. I never said that I would not eat this or that, and drank alcohol as freely as Germans (hard drinks, wine, beer all mixed up), but was never drunk.

We never separated into different groups by age. I never went for dancing or to clubs, though I had learned Fox Trot, English Waltz, Cha-Cha-Cha, Tango, etc. in Dresden. No, we talked, all generations sitting together, read books and went for walks – all together. Thus, Anne and her parents did not feel that I was from India, and was not German.

Anne, Anita and I went for holidays to Prague in 1966 and to Warsaw in 1967 – both cities belonged to the communist bloc. We stayed in youth hostels in separate rooms, and visited all cultural sites. Anne was very upset about the atrocities committed by Nazi German on the Jews, and wanted to undo the past. So we visited all places, where Jews had suffered and were aghast at what had happened during World War II. These short trips of 2-3 weeks were very fundamental in deepening my understanding of Europe.

In December 1967, Anne decided to move from Leipzig to Dresden, as a teacher of German (for foreigners) and Russian (for German students) at TU. Now Anne and I could spend more together. Anita was also working in Dresden and we met often. Gerlinde’s parents lived in Dresden, but she continued to work in Leipzig.

Trips to the West

Later, in 1968, I decided to make a trip on my own to Western Europe, which I had not done so far because I had almost no Western currency, had no friends or relatives in the West, and my knowledge about West was limited. I managed to exchange some money in the black market, got some Rupees from India, and decided to go to Switzerland via West Germany. I could buy the round trip train ticket in East German currency, so I needed money only for food and youth hostels.

In order to obtain the visa for Switzerland I had to go to their embassy in West Berlin, as the Swiss did not have an embassy in East Germany. Going to West Berlin was quick and easy. Indians had no trouble in getting the necessary exit visa from East German authorities. Once you had the visa, all you had to do was to take the underground train from Friedrichstrasse station in East Berlin to the centre of West Berlin, just a 10 minutes ride.

West Berlin was like a dream, so beautiful and so far ahead of East German cities in living standards. And, of course, the West Berlin workers did not think that they were being exploited\; instead, they felt sorry for the East Germans. There were huge departmental stores (malls) within walking distance. There were always things such as shirts, pens, bags, etc. on sale. One could change money in black in East Germany, converting 7 East German marks for 1 West German mark, though sometimes you could change money at 3:1 ratio. Even at the 7:1 ratio, things were still cheaper in West Berlin, and life was fast and colourful.

My destination in Switzerland was Grindelwald, a small town in the foothills of Jungfraujoch (3,471 m high) at the edge of the famous lake Interlaken. Along the way, I stopped in Nuernberg, Munich (all Germany), Zurich, Luzern, Interlaken (all Switzerland), and on my return in Frankfurt, Karlsruhe, and Kassel (all Germany). I stayed in youth hostels for the first time, a unique experience for me. I had some good discussions with the young people staying there, including one American, who later wrote many letters to me.

I was amazed by the train trip from Grindelwald to Jungfraujoch station. The train winds up in innumerable bends up to an amazing height, passing through several long tunnels. In September, the sun was shinning brilliantly, but it had snowed the previous day and the whole route was covered with snow. At the top, I could walk on a glacier and look at several alpine peaks. When I looked down, I could see a vast area of Switzerland sprawling in front, specially the lake Interlaken. I could not believe my luck!

Anne had guided me about what to see in West Germany. Following her advice, among other things, I went to the birth house of Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the famous German author, in Frankfurt, and visited the modern art exhibition in Kassel called Documenta.

In the beginning of 1969, I was elected as the President of the Association of Indian Students in Dresden. It was little more than a meeting place for friends with almost no external activity. But for the East German authorities, I was a politically significant person. I utilized this opportunity, and told the authorities that I had to go regularly to West Berlin to meet people in the Indian consulate. The East Germans issued me a multiple-trip exit visa, and suddenly I was travelling very often to West Berlin and could do a bit of shopping. You have to consider that even in 1969 ordinary household items such as butter or bananas were not readily available in most of the East German cities, and things such as cigarettes and perfume from West Berlin were highly welcome.

The struggle for the doctorate

Studying for Ph.D. was not easy for me. In Europe, you have to do it all by yourself. I shared a working room in the university with another Indian and an Indonesian research scholar. We could come and go as we liked, there was no schedule, no set times, no teaching, no guidance. The Indian education system did not teach me how to do research, which requires deep knowledge of your field, reading far beyond the university education. Further, in India, there was no requirement to get practical training by working in a factory during the summer break. Our Roorkee University teachers told us that we were going to be officers, which meant that we would only have to do deskwork as engineers, the practical work is carried out by workers.

So, I was at a bit of loss in the German system. Fortunately, my professor advised me to attend some lectures and take the exams, all in German. This I did with flourish. I sat with the normal students, did laboratory experiments with them, and sat for the exams with them. It was all new to me, but I did it well.

My professor was an expert on high voltage switchgear and had been working on the properties of SF6 gas, which had been recently discovered to be very suitable for quenching the arc in circuit breakers used in power systems. His vision was that this gas should enable one to reduce the size of a medium voltage CB to the size of a HRC fuse. I had to build such a CB, test it, and also theoretically explain why the smaller size was possible. Well, I had a hard time finding a suitable theory. More importantly, it was next to impossible to get such a CB built in East Germany at that time. I had to rely mainly on the institute’s workshop, which was outdated. There were no computers, no copying machines, no sensors, no measuring devices and no ...!

All factories in East Germany would do something for me – if only they could! My professor was ready to write recommendation letters for me, but no suitable factory could be located, even though I travelled up and down the country. Finally, I landed in a small workshop in the town of Zittau, in the southwest corner of East Germany, bordering on Poland and Czech Republic, very near to Goerlitz, where Anne’s parents lived. I had to make all the constructional drawings by myself, specify all the materials and tolerances (which required more chemical and mechanical engineering than an electrical engineer normally does). But East Germany was bankrupt in resources, and the workshop used what they had and did what they could.

Somehow, I finally constructed such a device, tested it in special laboratories in Berlin, and wrote an acceptable theoretical explanation for the performance. The device was bigger than I had wanted it to be but it was still much smaller than the normal CBs. I had to defend my thesis in front of a panel of professors, who accepted it. I was happy that it was over, though I had taken more time than envisaged.

A CB of the type I made sells today for more than US $ 50,000. They are made in world-class factories and not in universities!

Annemarie and I get married

By the beginning of 1968, Anne and I had decided that we were going to marry. By middle of 1968, the East German government told us that we could marry and that they would allow Anne to leave for India with me, but not to any western country. To get this approval, I had to prove that I was unmarried in India! I was also required to get permission from the Indian Government. The request was sent via the local government to the Indian Government, which contacted my parents. My father agreed to the request, though my mother had her inhibitions because she thought that her beloved son was lost for her and India! I had to go the Indian embassy in Prague to get the final approval from the Indian side, as there was there was no Indian embassy in East Berlin those days, just a consulate for visa purposes.

After getting the approval of two Governments, I delayed the wedding, hoping to finish my doctorate and start earning money before marrying!

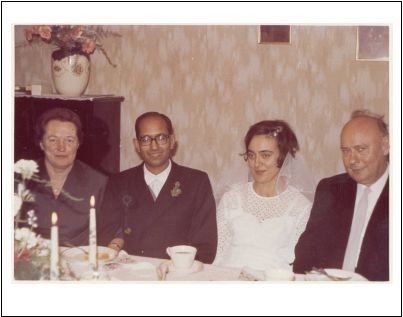

We got married on 1.2.1969 in Goerlitz. All marriages in East Germany had to be civil marriages, but in addition we went to a church. From my side Shrikant attended the marriage and all the girl friends of Anne were also there. In all there were not more than 20 guests, nothing compared to an Indian marriage. It was more like a party where you do a lot of talking with ever increasing level of alcohol in your blood. My in-laws spent all the money without mentioning even a word about it.

Married life in East Berlin

By middle of 1969, Anne and I had decided that it would be better for us to stay on in East Germany after my doctorate was finished. Our child was on the way, and she felt that conditions in India would probably be too harsh for a small European child. I had to accept her concerns.

My professor found out that I could work in East Berlin at Transformatoren Werke, which used be an AEG factory before WW II. They had a department for designing fully metal enclosed SF6-gas isolated high voltage switchgear. It was a new product and only Siemens, AEG and Brown Boveri were making such equipment in West. East Germany had the rights to make and export such equipment solely within the East European communist countries. I joined a new team of young engineers in November 1969, after I had completed my Ph.D. We designed the equipment, but did not reach production stage during my time there.

It was nearly impossible for an average East German citizen to permission to move from another city to work or live in East Berlin. East Berlin was a privileged city, with a much better supply of goods from State-owned factories. It had the highest living standard in all communist countries, including Russia.

Since I had been the President of the Association of Indian Students in Dresden, I had a known track record with the East Berlin authorities. They readily gave me the permission to work in Berlin. They also allotted a flat to me in the nice riverside district of Grünau, on the southeastern tip of Berlin, well connected by a fast electric train to the city centre.

The Dahme River passed just a few yards from our house. There was a regular ferry service to the other side of the river, where there were nice restaurants. We also had woods close to our home, where we could go for a walk. Grünau was a small village, which had become a part of the big city. It was quite and calm, and yet in Berlin.

Sunita was born on 24th March 1970 in Goerlitz, Anne being at home with her parents. She shifted from Goerlitz to Berlin in summer 1970. She had quit her job in Dresden and was not working any more. But only I had permission to live in Berlin – she did not! She lived there without permission, and we hoped not to get into any trouble.

My mother-in-law loved that we were in Berlin. She came by train almost every month, bought foodstuff for us, and filled our refrigerator without asking. She loved to go shopping in Berlin and loved to play with Sunita.

I obtained another multiple exit visa for West Berlin, and started going there frequently. Shrikant had finished his doctorate earlier than I had, and had found a job straightaway in West Berlin. So I visited him. On these trips, I smuggled paperback books written by famous German authors such as Thomas Mann, Heinrich Heine and Kurt Tucholsky. They were not available in East Germany and Anne wanted to read them. I hid the books somewhere in my clothes, and made sure I always brought some permitted items with me, which I showed openly to the border authorities. This created the impression that I was honest and they did not search any further.

Escape!

In the beginning of 1971, Anne and I decided that I should try to get a job in the West instead of going to India. Even my relatives in India were expecting me to have a job in the West.

Thus I had to get a job in West without the East German authorities knowing about it. I could not mail any applications from East Germany to western countries because the authorities opened all letters, those coming in and those going out. So, I took my letters (applications for jobs) to West Berlin and posted them there, using Shrikant’s address as my address. Since all replies came to him, I visited him often, at times almost everyday – remember that West Berlin was only a ten-minute train ride form East Berlin.

In June 1971, Brown Boveri Company (BBC) in Vienna/Austria offered me a job. We were delighted! But we had to keep it a secret, and told no one about it. In July 1971 I travelled to Vienna for the interview. The head of the department came to pick me up from the railway station. In the office, we had only a cordial talk, no interview as such. They not only offered me a job but also a company-owned flat to live in for free. There was a dearth of qualified people in Austria in those days, and they were eager to have me. I told them that I could join them in October and they accepted that. The head of department took me to the railway station and I returned to Berlin the same day.

Anne and her parents were thrilled, as they had never thought that they would live in Vienna one day. My father-in-law knew about the great musical past of Vienna - Vienna used to be one of the cultural centres of Europe. But we were still not there, and we wanted to avoid going to Vienna via India.

We made a plan. I would go to Vienna by train, but tell everyone that I was going to India, no mention of Vienna. Anne and Sunita would fly to Vienna en route to India, without a visa for Austria – they would be only transiting through Vienna. Since Interflug, the East German airlines, did not fly to India anyway, it seemed reasonable to fly with them up to Vienna. We told Interflug that the tickets from Vienna to New Delhi would be waiting for Anne in the transit zone in Vienna. Anne had no problems in purchasing the air tickets to Vienna for herself and Sunita in Berlin.

In Vienna, the West Germany embassy people told me that they were more than willing to give West German citizenship to Sunita and Anne as soon as they came to their office. The West German government had the policy to encourage East Germans to escape to West Germany\; West Germany never recognized East Germany. Further, I visited the Austrian authorities and told them that my wife would fly in from East Berlin, and asked them to allow Anne to enter Austria, although she did not have a visa for Austria. In those Cold War days, this was no problem for the Austrians, as Czechs, Hungarians and Germans were daily crossing the border illegally in to Austria. Austria not only welcomed them but also gave them citizenship and Germans were more welcome than other nationalities.

In order to inform Anne about the arrangements I had made in Austria I spent my Christmas-New Year holidays of the year 1971/1972 in Goerlitz\; I travelled from Vienna to Goerlitz by train. At the border, they treated me as if I had never lived in East Germany! They had no records, no system for checking the past.

On the critical day in February 1972, the Austrians allowed me to go deep inside the airport and to wait at the passport control desk. When Anne and Sunita came, I pointed them out to the authorities, and they let them enter into Austria without any fuss. What a day that was!

Epilogue

A police officer had visited us in summer 1971. He said that he had come to find out why Anne was staying in Berlin without permission. He said that he would help us get the permission for her. Luckily, Anne had applied for a visitor’s permission shortly before he came, so she was not there illegally at the moment and his help was not required. We also told him that we were going to India soon anyway.

I had forgotten the above episode. However after the reunification of East and West Germany, the German government has opened files of the STASI (state security) and only recently I have received a 75-page document from them. It is mentioned there that the police officer was actually a STASI spy who wanted me to become an IM (informal member), a code word for an East German spy, and help gain Shrikant as a spy operating from West Berlin for them. He had come to evaluate me, and all his talk about permission for Berlin was empty talk.

There was a lady in our building who maintained a list of all occupants in all the flats\; visitors who stayed for a long time also had to sign in a book she kept, just as in a hotel. She must have told the police that Anne was staying illegally in East Berlin.

East Germany was full of spies and we were happy to end that chapter.

© Kailash Mathur 2008

Comments

Add new comment